SunShip Thesis

-

Fragments on Crisis, Loss and the Pandemic

Terri Abruzzo

The paradox of living through this pandemic time is that everyone on earth is experiencing this crisis, yet it is uncommon to the vast majorities of humans alive today (there are 90,000 American centarians who were alive during the Flu Epidemic of 1918). Yet despite the collective nature of the experience, it is different for everyone due to personal life circumstances.

Notions of crisis, both global and personal, have been on my mind. The last eighteen months highlighted the macro and micro ramifications of crises when the Covid 19 pandemic and its accompanying lockdowns were overlaid on my beloved father’s dying of heart failure. At the same time, I left my longtime legal practice in Chicago, Illinois. For the last few years, I had been representing refugees and asylum seekers, for whom the global crisis of migration impacts individual lives in profoundly disparate ways. My fresh freedom from corporate strictures and thinking encouraged me to leave formal, mechanistic legal writing behind in favor of the creative exploration and writing that fueled my childhood.

Through the darkness of the lockdown and civil upheavals of the summer of 2020, I was bolstered by virtual talks hosted by Arts Letters and Numbers. I knew ALN’s virtual studio, Thesis, would be a delicious soup of ideas and questions and a great place to explore concepts of crisis, human response to crisis and the losses of this year.

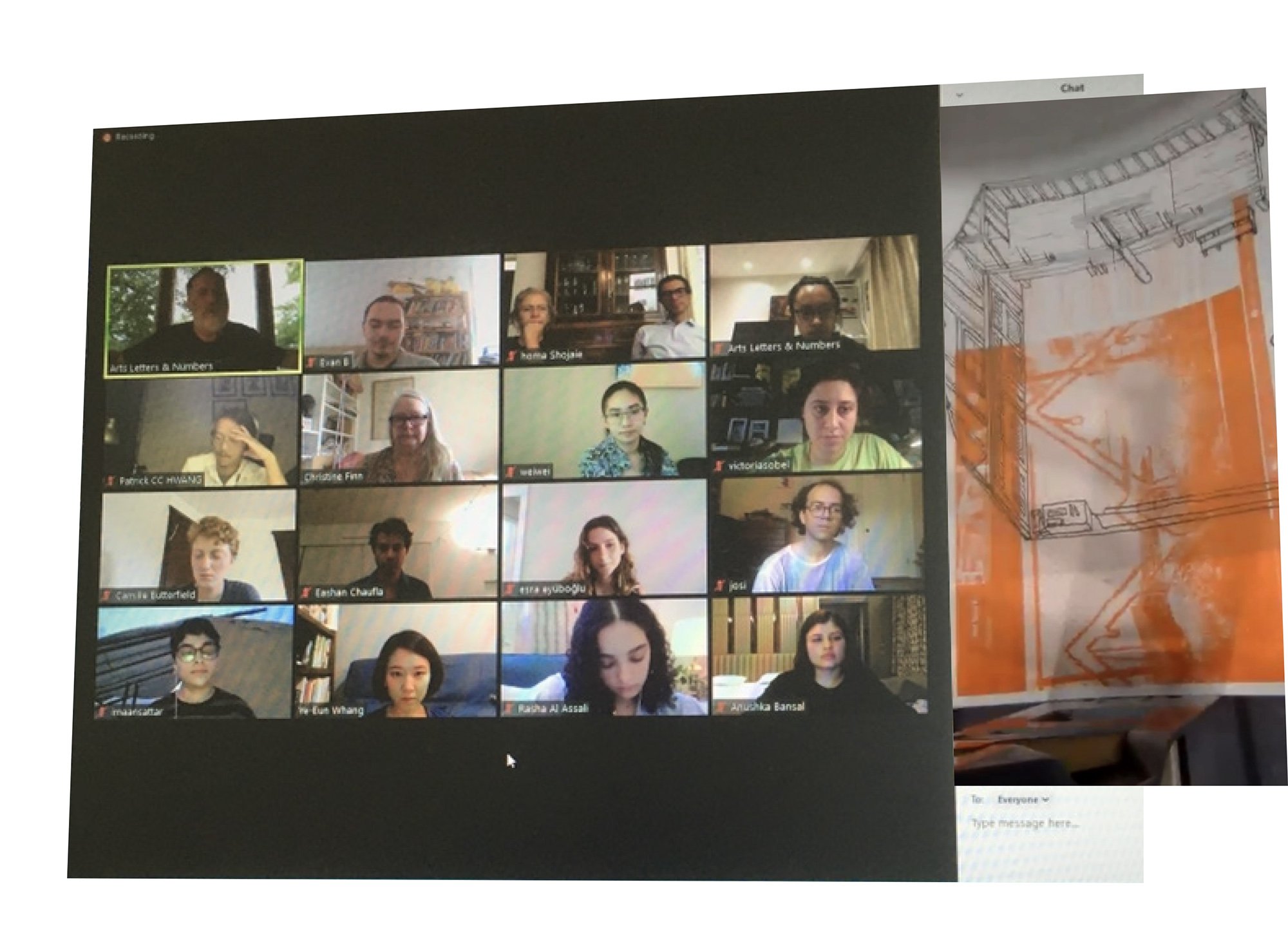

The six weeks of Thesis unfolded each week in the Listening Sessions as a spotlight shined into the different squares on our Zoom grid, illuminating each participant’s creative world. Geographically and experientially different, each participant came with their own set of materials and interests, keeping the sessions alive. Our digital grid felt like a repository of trust and encouragement.

I created a PowerPoint presentation called “Fragments from an Erstwhile Lawyer and Practicing Human (Poetics in PowerPoint.)” Using some personal photographs and other images, I wrote and talked through the issues and memories I have been grappling with throughout our virtual studio. I then tried to convert this PowerPoint into a written piece—this document. During my final presentation, David Gersten, ALN’s founder, was forced to zoom on his phone when his computer died. Visiting artist, Tine from Denmark, held up her computer to the screen so he could see the full group. We had talked throughout Thesis about the concept of “living in the still life” and I was struck by the meta nature of that visual. Here is a picture I snapped of that moment.

“What we learn in time of pestilence: that there are more things to admire in men than to despise.” Albert Camus, The Plague

sharp as a scalpel…

a mosaic of macro-musings on

Crisis…Loss …Space and TimeThe global Covid-19 pandemic is a crisis that, while impacting the entire world, was and continues to be, experienced entirely individually, depending on one’s personal life circumstances. You may have heard this quote: “When written in Chinese, the word crisis is composed of two characters. The first represents danger and the second represents opportunity.” This quote is a darling of personal development gurus and politicians like Al Gore, who used it often in reference to the climate crisis. And, as the storm clouds of the pandemic gathered then burst in 2020, I felt like I read it everywhere. It seems like a harmless phrase intended to inspire and encourage, and yet…according to Victor Mair, a professor of Chinese language at Penn, ascribing this meaning to the Chinese word for crisis is incorrect. Mair pointed out in a 2009 article that while the first character “Wei” does mean danger, the second character “ji” does not mean “opportunity.” Rather, it means a time of difficulty, insecurity, and suspense when things can go awry. Ji” simply means a dangerous moment, an incipient and crucial turning point with none of the auspicious, favorable connotations that the word “opportunity” implies.

At best, this is an example of imprecision, at worst, a pernicious misuse and misappropriation of language. This interpretation is a capitalist commodification of the phrase. It encourages people to welcome crises as unstable situations with the potential for personal benefit rather than to work to solve the crisis in a way that would distribute benefits across the whole community or population. Never let a good crisis go to waste, and all.

A capitalist perspective was prevailing in the early days of the COVID pandemic. In the initial throes, many looked to exploit the crisis as an opportunity to make money. We saw price gouging on masks, ventilators, and other personal protective equipment. We saw Amazon’s mutation into an earnings superpower overtaking Walmart for the number one spot and bankrolling Jeff Bezos’ trip to the edge of space.

But when individuals focus on personal, material gain without considering the impact on the collective, a crisis often gets worse. Commodification of or highly individuated responses to global inflection points impede deeper, more holistic problem solving that a crisis demands.

However, there is another perspective on any crisis, especially a global one like the pandemic, climate change or the migrant situation. Instead of blindly accepting a capitalist approach, we should be asking, how do we find the global as well as individual opportunities that posit a new, better way of being for all the humans inhabiting earth? Ultimately, “How do we encourage action in a crisis that benefits the community, the collective, rather than simply the 1% or those aspiring to be?”

To encourage action that serves the many, not just the few, it is necessary to set aside the capitalist perspective and reconceive time. A long, biblical view of time, a “cosmological” or “collective” perspective, where humans can see beyond their own circumstances and lifetimes in order to work to bend the moral arc of the universe toward justice would yield outcomes more likely to benefit the collective. If we instead focus on the blink that is a human lifetime, the collective good likely will be minimized as each person acts out his or her version of maximizing the brief time we have on earth.

Milton Friedman endorses the marketplace of ideas and the need to think through solutions and have them on the shelf before a crisis strikes: “Only a crisis-actual or perceived- produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes the politically inevitable. “Capitalism and Freedom, University of Chicago Press 1962.

When I took a class on Transcendental Meditation, my father gifted me (somewhat tongue-in-cheek) Marcus Aurelius’ book of Meditations. A central theme to Meditations is the importance of developing a cosmic perspective. Aurelius states: “You have the power to strip away many superfluous troubles located wholly in your judgment, and to possess a large room for yourself embracing in thought the whole cosmos, to consider everlasting time, to think of the rapid change in the parts of each thing, of how short it is from birth until dissolution, and how the void before birth and that after dissolution are equally infinite.” Marcus Aurelius, Meditations.Encouraging this cosmological or collective perspective is not a simple task. How do we contend with the fact that at some point, capitalist ideals and material success supplanted collective good and became equated with greater rights and moral superiority? Are these ideals so baked into our American society that there is no turning back? The past demonstrates that a purely capitalist perspective does not always prevail. Historically, the types of conditions we saw during the pandemic (e.g., “essential workers” being subject to the risk of harm without their consent or commensurate increase in wages) led to great labor upheaval like the 19th Century Haymarket Riots in the United States. This similarity begs the question whether “collective bargaining” has diminished along with concern for the collective.

A New Social Contract: WE Over ME in an Interdependent World

In all societies, some things are left to individuals and others are determined collectively. The norms and rules governing how those collective institutions operate is the social contract, the most important determinant in the kinds of lives we lead. Because it is so important and because most people cannot easily leave their societies, the social contract requires the consent of the majority and periodic renegotiation as circumstances change. What We Owe Each Other: A New Social Contract for a Better Society, Minouche Safik, Princeton University Press, 2021. In order to address global crises like the pandemic, climate change and displaced persons, we need a new social contract or at least to revisit and rethink the old one.

Minouche Shafik has been the Director of the London School of Economics since 2017, and her “curiosity about the architecture of opportunity” led to a career that spanned the World Bank, the UK Dept. for International Development, the IMF and the Bank of England. She recently imagined the kinds of policy prescriptions needed to keep our fragile world from pulling apart in her book What We Owe Each Other: A New Social Contract for a Better Society, Princeton Press, 2021. She wisely notes that though many go through life thinking themselves “self-made” or credit/blame their families for their lot in life, the bigger forces that determine our destinies: the country we happen to be born in, the social attitudes prevalent at a particular moment in history, the institutions that govern our economy and politics and the randomness of just plain luck, are rarely considered. Every country is distinct, especially on issues such as the balance between the individual and the collective. Countries like the U.S. put greater emphasis on individual freedom, whereas Asian countries prioritize the collective interest. Europe tries to strike a balance somewhere in the middle.

Yet, despite the huge material gains the world has seen in the last 50 years, surveys show that 4 out of 5 people in the U.S., Europe, China, India and various developing countries believe the system is not working for them. Shafik argues we need a social contract that delivers a better architecture of both security and opportunity. She lays out the challenges we face and provides a menu of alternatives for a better social contract around families, education, health, work, old age and between generations, encouraging a shift in values to think more about “we” and less about “me.” She advocates investing in people and proactively planning these changes rather than reacting with actions based on, to quote Milton Friedman, the ideas we have lying around. For example, she recognizes the power of education in solving worldwide problems as well as its power to lift each individual in the process and proposes granting each person $50,000 for education to be spent in his or her lifetime, framing this as providing opportunity and individual sovereignty rather than welfare.

Her chapter on the contract between generations and the environmental legacy we are leaving provides a perspective both thoughtful and sobering. She notes that economists think about the inheritance of each generation in terms of the three different types of “capital” that determine the productive capacity, or wealth, of a country: 1) human capital (educated people and the institutions and social structures they create); 2) produced capital (technologies, machines, infrastructure); and 3) natural capital (the climate, biodiversity, land.) While changes to human and produced capital are often reversible (people can change their minds and invest more or less over time), changes to natural capital can be irreversible. Yet, her research shows that each person in the future will inherit twice as much produced capital, 13 percent more human capital, but 40 percent less natural capital. She asks: Does that pattern leave future generations better off?

We know that a hotter planet impacts the world’s water in the form of floods, droughts, storms, desertification, ocean acidification and sea-level rise, all with potential for devastating effects on human well-being. Similarly, biodiversity is being lost faster than at any time in human history. Accordingly, depleting natural capital should be done with a keen awareness of the risks of extinction and careful consideration for highly interdependent ecosystems.

Shafik points to the UN’s definition of sustainability used in developing the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, and I agree it is the most succinct and workable definition: “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” However, she also notes that economists historically discount future generations relative to those alive today and that this plays a central role in a hesitancy to act on climate change. Her prescriptions for environmental redress include: 1) first, do no more harm; 2) invest in restoration and conservation of biosphere; 3) use better calculations to accurately value the services that nature provides and the costs of depletion; 4) use fiscal policy -tax and spend- to incentivize, including compensating low-income populations for disproportionate impacts on them.The success of the prescriptions in Shafik’s book rests largely on the recognition of the interdependence of human beings around the world and indeed with the earth itself. We cannot separate our community or country from what is happening in other parts of the world.

“No One Puts Their Children in a Boat Unless the Sea is Safer Than the Land”

Migration and Refugees: A Crisis Both Macro and MicroIt is my hope that in discussing my pro bono work with refugees and asylum seekers, I will be “speaking nearby” rather than “speaking about” as that expression is used by its creator, filmmaker Trinh Min-Ha. Min-Ha notes that “it is very comforting for a reader to consume difference as a commodity by starting with the personal difference in culture or background, which is the best way to escape the issues of power, knowledge and subjectivity raised.” She advocates a speaking that does not objectify, does not point to an object as if it is distant from the speaking subject, that reflects on itself and can come very close to a subject without seizing or claiming it. It is also important to me to note that my client and friend Mujtaba gave me express permission to share his story in this context.

Mujtaba was an interpreter for U.S. and NATO forces fighting the Taliban like 50,000 others who helped the US in Afghanistan with the understanding that they would be protected with special immigration visas or SIVs. Unfortunately, a process supposed to take 9 months at the most often dragged on for years. When Taliban forces began threatening my friend’s family, they tried to escape across the Mediterranean on a boat. The boat capsized in the waves and his wife and two children were lost at sea. My friend and his surviving son were sent to Turkey which is when I got his case. We could not restart his SIV process at first because he spent his days scouring refugee camps and websites for his lost family members. He was certain that a voice he heard on a Facebook video taken in the refugee camp Moria in Greece was his daughter, even after it was verified to be someone else. He could not move forward because he wanted so badly to believe his family members were still alive somewhere. When he ultimately decided that resettlement did not mean he was abandoning his lost family members, we finally secured his Special Immigration visa and Mujtaba and his son resettled into a community in New York. In a bit of serendipity, they originally were to be settled in Albany and I was thrilled thinking that I could see them when I came to ALN. Ultimately, however, they were resettled in Rochester.

Migrants’ stories like this one can be quintessential stories of crisis and loss, displacement in time and space, as well as resilience and recovery. The powerful Ai Wei Wei film, The Human Flow, captures the scale and personal impact of the global refugee crisis – at its heart a massive human migration. It contains many visuals that portray the magnitude of this issue on the macro and micro level, but one will stay with me always, so moving was it in its simplicity. It is an aerial shot of a large orange vessel in the middle of the ocean. As the camera pulls close enough to the sea that one can see the waves, it becomes clear that the vessel itself is not orange but rather is filled with tightly packed individual human beings all wearing orange life vests. What an incredible metaphor for recognizing each individual story comprising an issue that has become both monolithic and a political third rail. As my client Mujtaba said, no parent would ever put their child in a boat on the ocean unless it was safer than remaining on the land.

Ai Wei Wei explained the significance of his title, Human Flow, and how it relates to flooding. He uses the analogy of either building a dam to stop the flood, which would not solve the issue entirely and could intensify the outcomes, or instead finding a path to let the flow continue. Relating dams to physical borders and walls, he encourages understanding the reasons people become refugees and working to ameliorate the underlying causes to stem the flow at its source.

A former Afghan interpreter resettled in Sacramento called the poorly handled departure from Afghanistan in August 2021 “a slap in the face”, as well as “a big lesson for other nations fighting for the United States” that the U.S. can’t be trusted, and they will “leave you in hell.” LA Times 8/21/21

I was asked in 2019 to speak about the case to the Immigration Law society at the University of Chicago. After my presentation, a student asked if we really thought it was a good use of my law firm’s resources to spend so much money on one man and his son. I told him that I did not see this case and my clients in terms of economic. The fact is that a poetic framework seems more appropriate to me in these circumstances.

The poem below is by Warsan Shire, a Kenyan born to Somali parents who was the Young Poet Laureate for London. She was inspired to write it by a visit to the abandoned Somali embassy in Rome which some young refugees had turned into their home. The night before her visit a young Somali had jumped to his death off the roof. Shire states she wrote the poem “Home” for them, her family and anyone who has experienced the grief and trauma of the refugee experience.

Home

Warsan. Shireno one leaves home unless

home is the mouth of a shark

you only run for the border

when you see the whole city running as wellyour neighbours running faster than you

breath bloody in their throats

the boy you went to school with

who kissed you dizzy behind the old tin factory

is holding a gun bigger than his body

you only leave home

when home won’t let you stay.no one leaves home unless home chases you

fire under feet

hot blood in your belly

it’s not something you ever thought of doing

until the blade burnt threats into

your neck

and even then you carried the anthem under

your breath

only tearing up your passport in an airport toilets

sobbing as each mouthful of paper

made it clear that you would not be going back.you have to understand,

that no one would put their children in a boat

unless the sea is safer than the land

no one burns their palms

under trains

beneath carriages

no one spends days and nights in the stomach of a truck

feeding on newspaper unless the miles travelled

means something more than journey.

no one crawls under fences

wants to be beaten

wants to be pitied

no one chooses refugee camps

or strip searches where your

body is left aching

or prison,

because prison is safer

than a city of fire

and one prison guard

in the night

is better than a truckload

of men who look like your father

no one could take it

no one could stomach it

no one’s skin would be tough enoughthe

go home blacks

refugees

dirty immigrants

asylum seekers

sucking our country dry

niggers with their hands out

they smell strange

savage

messed up their country and now they want

to mess ours up

how do the words

the dirty looks

roll off your backs

maybe it’s because the blow is softer

than a limb torn off

or the words are more tender

than fourteen men between

your legs

or the insults are easier

to swallow

than rubble

than bone

than your child body

in pieces.

i want to go home,

but home is the mouth of a shark

home is the barrel of the gun

and no one would leave home

unless home chased you to the shore

unless home told you

to quicken your legs

leave your clothes behind

crawl through the desert

wade through the oceans

drown

save

be hungry

beg

forget pride

your survival is more important

no one leaves home unless home is a sweaty voice in your ear

saying-

leave,

run away from me now

i dont know what i’ve become

but i know that anywhere

is safer than hereThe Scourge of “I”: You Can’t Have a Refugee Crisis if You Don’t Have Refugees

In a crisis like Mutjaba’s and the one I discuss below, I agree with Manouche Safik that we all need to be ready to do what we can to help others– a ”we” instead of “me” mentality -beyond the immediate circle of our own families or immediate communities. Immigration crises are increasingly recurring and global circumstances suggest this will continue. In addition to planning for safe and controlled migration like Ai WeiWei advocates, we all need to be willing to pitch in and extend ourselves personally to help individuals that but for the grace of God could have been us. I remember reading that a classic test for creating societal rules should be whether you would vote for it blind to the station you would be born into in life.

How did we get so disconnected from the humanity that connect us all? A friend referred to it as “the scourge of the “I”. I as center of the universe. I am entitled to do what I want without regard to others. I no longer have a dream about a better life for a collective group of people because I can hop on my iPhone and scroll through social media feeds that reinforce what I already think and “eye” things I can buy that will distract me from reality with the endorphin hit of consumption.

On January 27, 2017, shortly after his inauguration, President Trump signed an executive order known as the “Muslim Travel Ban”, which halted all refugee admissions into the United States and temporarily barred people from seven Muslim majority countries. Trump signed the order on a Friday afternoon and by Saturday it was clear that there were people traveling who would have their status affected while in midair. On Saturday morning, I went to O’Hare International Airport in my hometown of Chicago and joined lawyers in about a dozen airports around the country – attorneys from many different law firms and nonprofits, coming together in teams– to file individual petitions to protect people arriving who had been in the air when the executive order was signed and to prevent elderly or other weary travelers from being held in secondary detention against their rights.

We set up a makeshift workspace in international arrivals right next to the McDonalds and I thought, “Justice smells like greasy fries.” The dynamic between what was happening inside the terminal with attorneys ready to go with habeas petitions, motions, and preliminary injunctions, and outside with massive protests and people holding signs and chanting, felt like democracy in action. Mayor Emmanuel showed up and thanked the lawyers. The ACLU and other nonprofits were working remotely with the lawyers on the ground at the airports. There were no templates on the shelf ready to go. Rather, people came together in an emergency, a crisis, to figure out a response as quickly as possible to protect people they had never met. What started as a group of 7-10 people at O’Hare organized into a mobilized group of over a thousand lawyers. That email thread exists to this day and is used as a network to help individuals and families experiencing immigration crises–all on a pro bono basis. A testament to the power of the collective, of we over me.King Croesus, My Father and Loss:

Count No Man Happy Until the End is KnownMy father was an ardent and enthusiastic student of history. The word history comes from the Greek “historia” meaning “inquiry” or “knowledge acquired by investigation.” Herodotus (484-428 BC) coined the term history to mean research or study and, indeed, from the time I was very young, my memories of my father are of him deep in thought with a thick history book in his hands. I wrote short stories about this when I was eight, which my mother recently found and gave to me.

Several years ago, to stave off the tedium of raising small children while I was on leave from my law firm, I enrolled in The University of Chicago’s Basic Program for Liberal Arts and studied the ancient Greek classics. One of my teachers’ favorite works was the Histories of Herodotus, in particular Book One and the story of King Croesus, the ancient king of Lydia.

As Herodotus tells it, King Croesus was once visited at his palace by Solon, a wise sage and Athenian lawgiver. The king was delighted to have the itinerant philosopher in residence and welcomed him with warm hospitality. Croesus instructed his servants to show off the full measure of the king’s enormous power and wealth. Once he felt Solon had been sufficiently awed by his riches, Croesus asked him: “Who is the happiest man you have ever seen?” certain that he would hear his own name. Solon, however, was not one for flattery and answered with the names of three common men who had lived and died honorably.

King Croesus was livid and could not understand how three dead nobodies were happier than he with all his power and riches. Solon explained that while the rich did have some advantages over the poor – “the means to bear calamity and satisfy their appetites”- they had no monopoly on the things that were truly valuable in life including civic service, being self-sufficient, and honoring the gods and one’s family. More importantly, Solon continued, not a single day in life is the same as the next in what it brings. In other words, just because things are going well today, doesn’t mean they won’t fall apart tomorrow. Thus, a man who experiences good fortune can be called lucky, but the label of happy must wait.

The king dismissed Solon as a fool and put his words out of his mind until tragedy fell. His beloved son died in an accident and Croesus embarked on an ill-advised war and ultimately was burned at the stake. As the flames began to lick at his feet, Croesus cried out, “Oh Solon! Oh Solon! Count no man happy until the end is known!”

Happiness according to the ancient Greeks differs from our modern-day associations with the word. Happiness was not a variable emotional state to the Greeks but was encapsulated in the concept of “eudaimonia,” which best translates as human flourishing, based on an assessment of whether a person attained virtue and excellence with respect to family, health, self-sufficiency, and honor. Aristotle used the term to mean “the highest human good” and according to Aristotle, the highest aim was to achieve it and spend one’s life studying how to achieve it…

Until the end is known….

For my Dad’s 80th birthday, I created a memory book of his life. Although he was sick, we did not know at the time it would be his penultimate birthday. On each of the many pages was a letter and photographs from all the most important people in his life, reflecting back to him all the love he emanated so profusely for eighty years. The book told the story of his life as an educator, a historian, a reader, a profoundly beloved husband, father, grandfather, son, uncle, friend. In its final form, it was the size of a phone book for those old enough to remember those.

With the end of his life near, unbeknownst to us, Dad himself filled in the ending of his book of life to demonstrate what he held most dear. He took the things he carried with him in his wallet and added them to the very last page. I saw these for the first time leafing through the book after he died. There are photographs of him and Mom at two of the many high school dances they attended when he was principal (they joked that they would never graduate and they could never stop going to prom-always with the same date), a dog- eared photo of Mom she sent when she was waitressing on Cape Cod one college summer (and rumors reached her that her sorority sister had designs on Dad) and Canadian money from their honeymoon in Niagara Falls. He always said that her love was the most important thing in his life.

In our Thesis seminar, we’ve talked a lot about cognition and recognition–how we know the things we know. When Dad got the news from his doctors and tuned into the signs his body was giving him, he cognitively understood that his time on this earth – all the summer days, old movies and favorite cars, first love and young children, politicians to hate and politicians to revere, books to read and ideas to discuss – all that and more was coming to an end. And in recognition of this impending loss, and the realization that nothing further was available to help his heart repair…he began to prepare. He organized his possessions, he expressed his love to all his family members, and he told us repeatedly, he had been very lucky, and he was happy. -

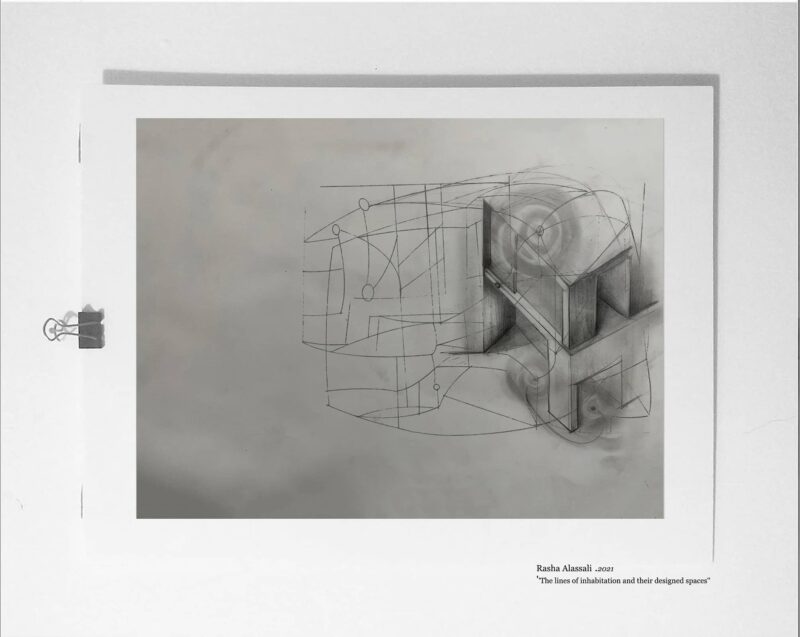

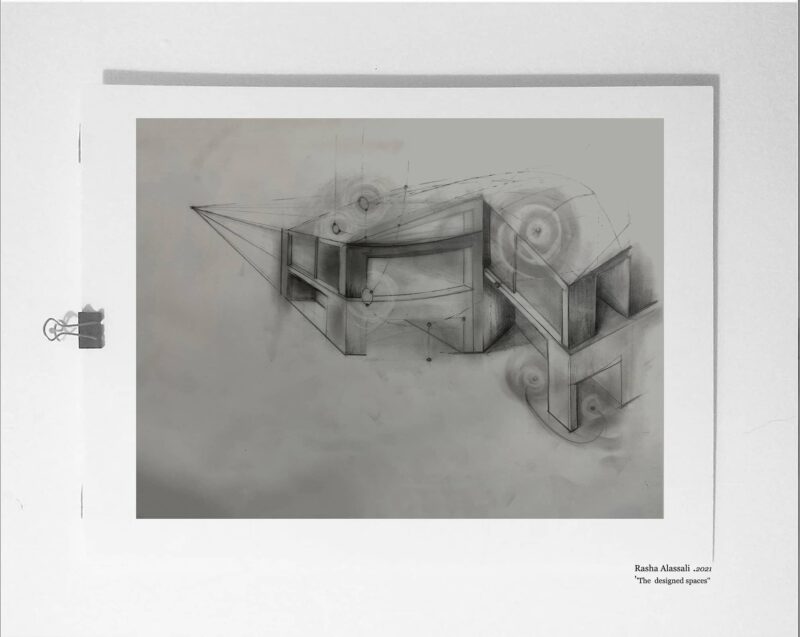

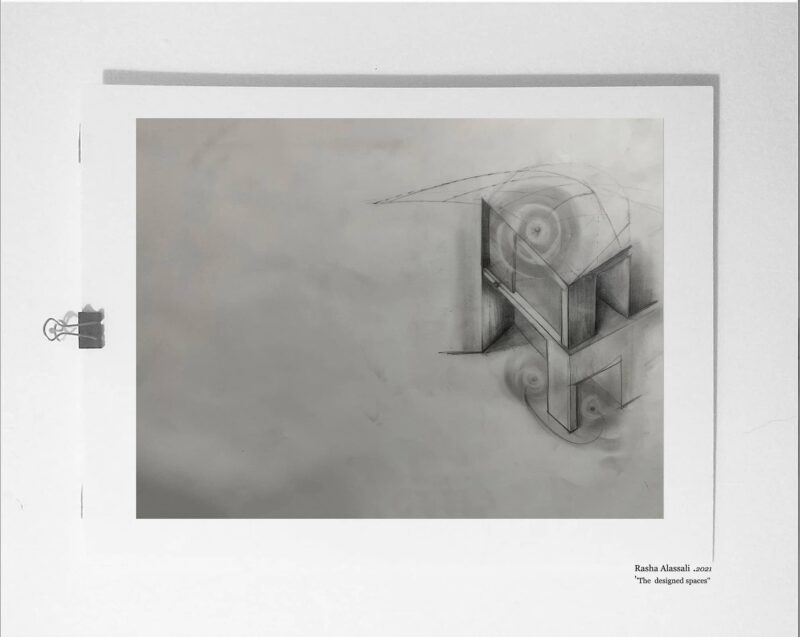

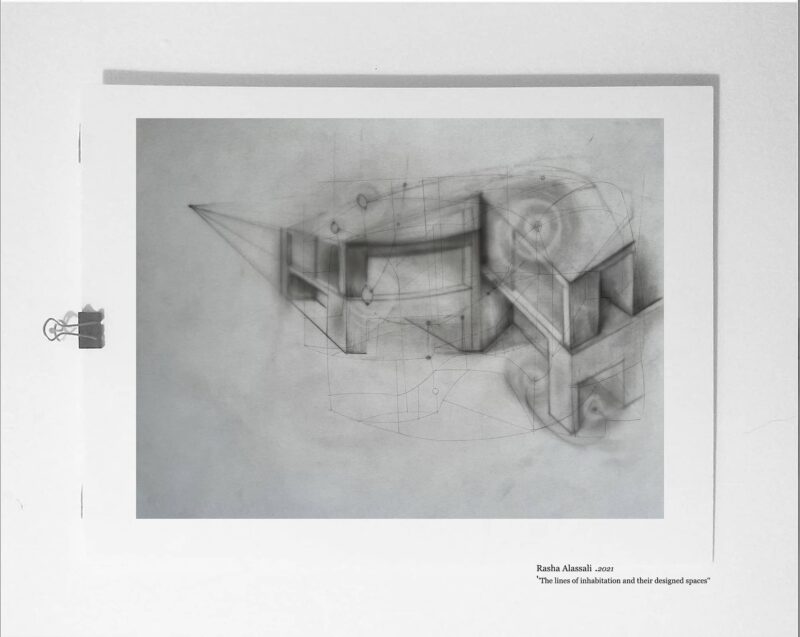

‘’The Dream of Inhabitation’’

For Sedu

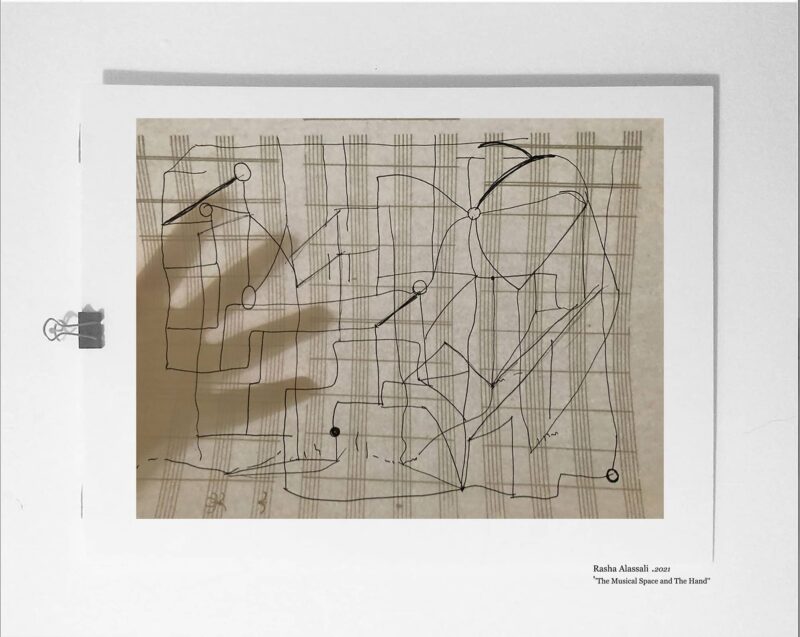

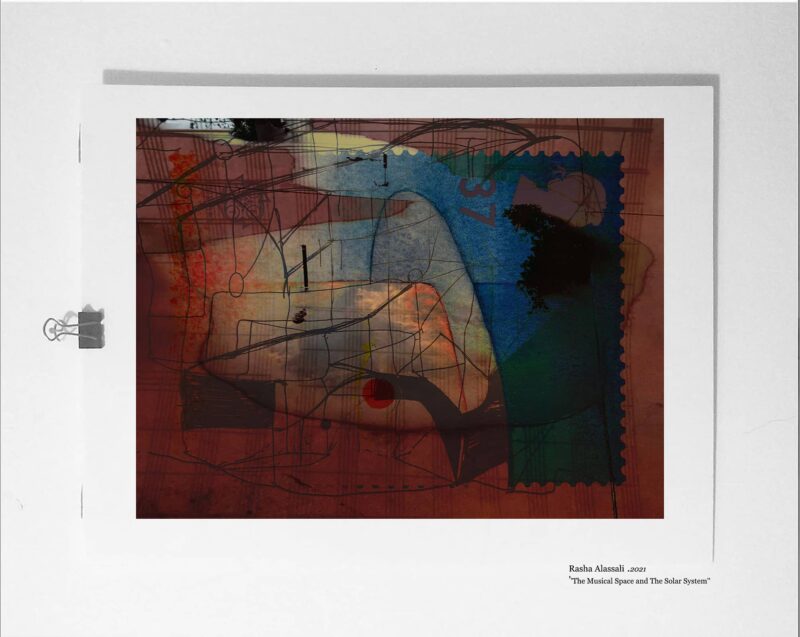

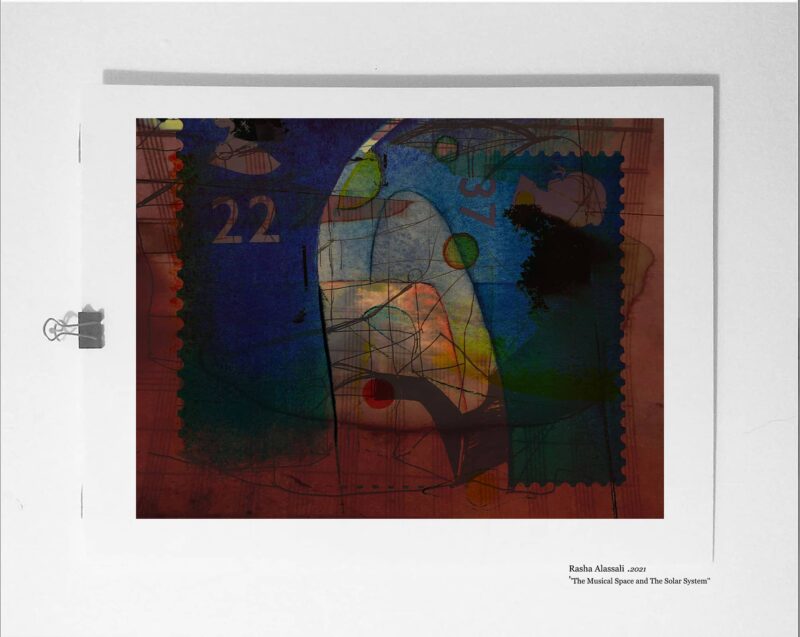

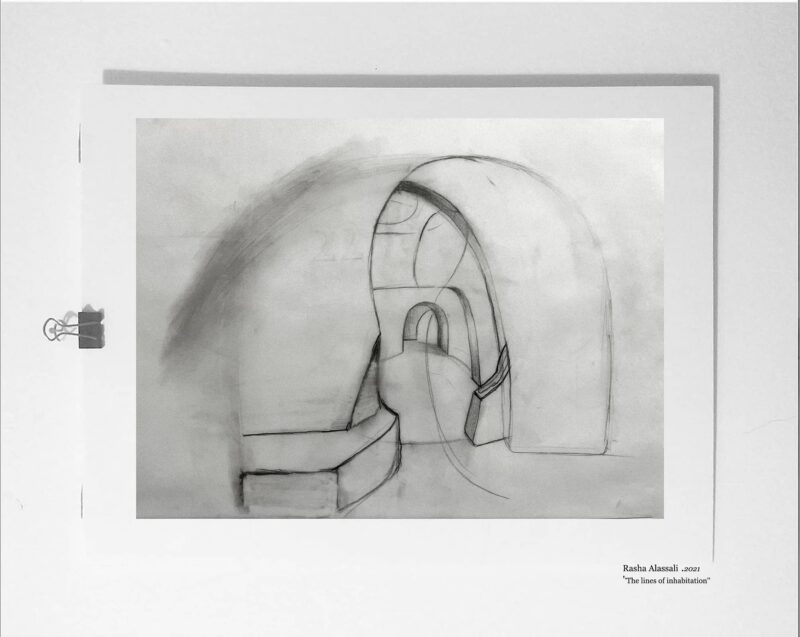

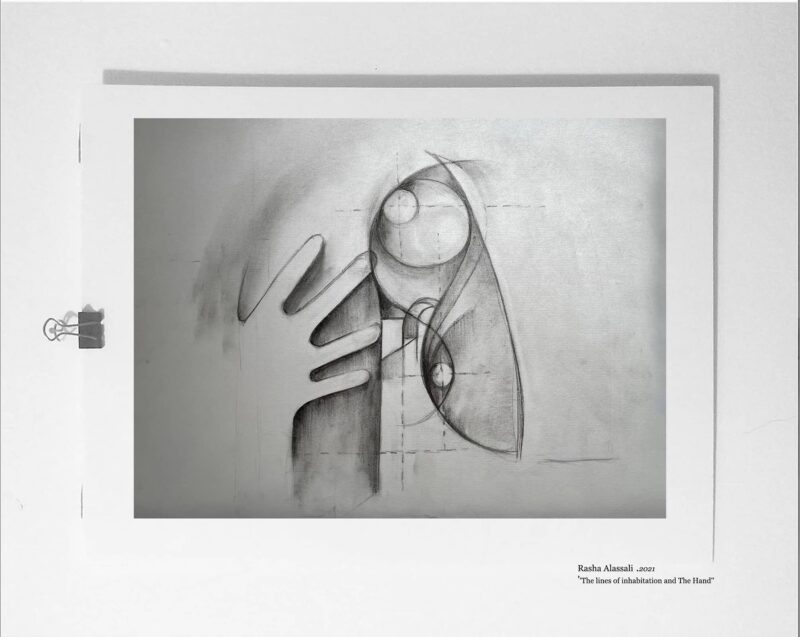

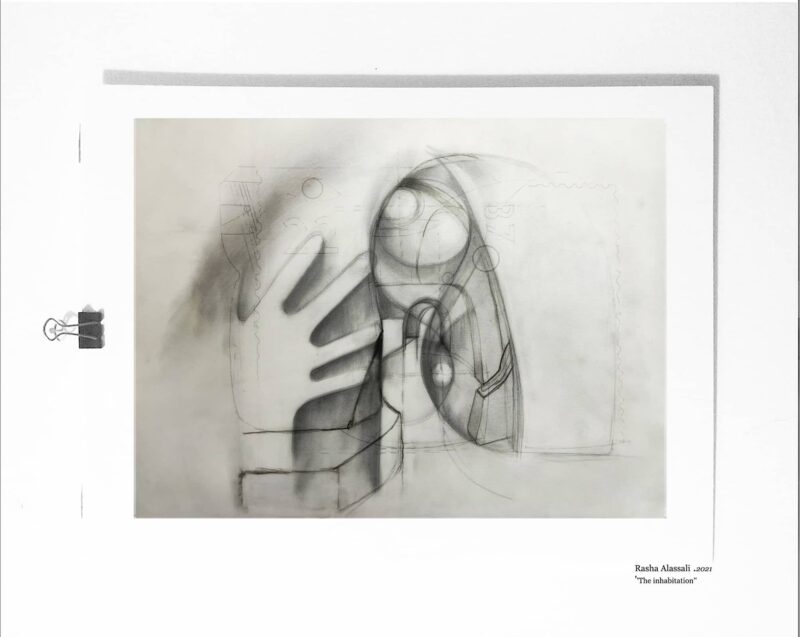

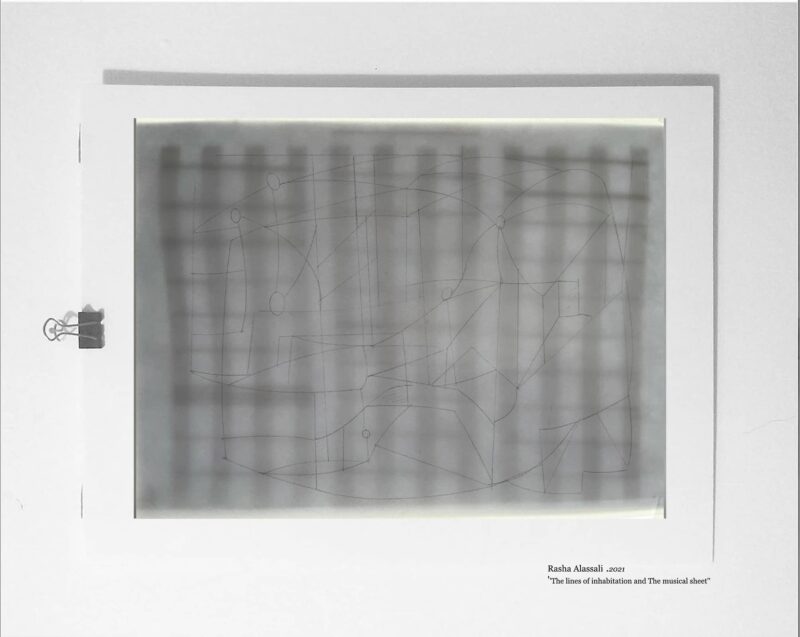

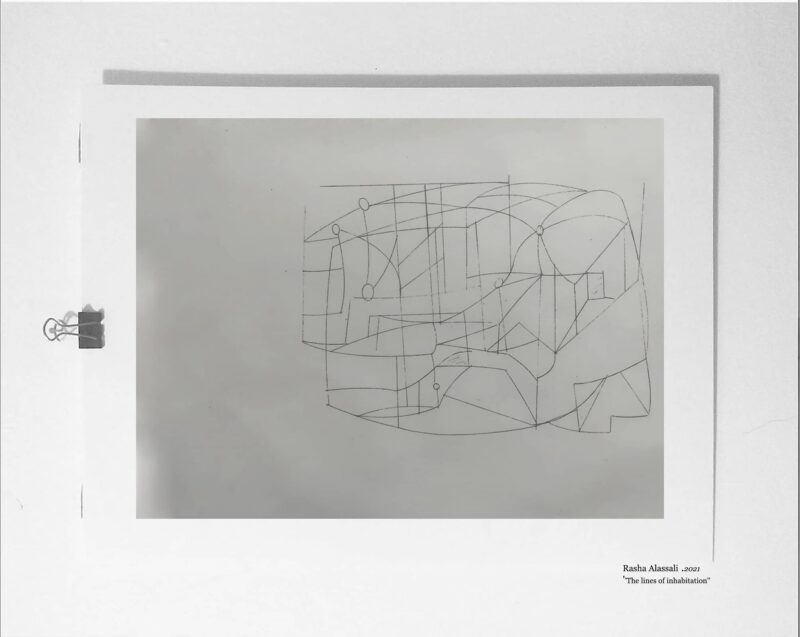

The point is the inner concise point of our being – it is small and circular, but it can transform into unlimited shapes that can be deformed or elongated to form lines, curves, and multiplied to several points. Several points are several circles. They create ‘The Cosmos’, that are composed of planets, the sun, the moon, and asteroids. Additionally, the point and geometries, in general, are inner attributes that mold us. For example, on the floor, we leave a trace of points where the dynamics of movement can construct points, lines, and curves, where these geometries can be a way to translate movement, into either mobility or immobility. Rigid immobility of a body can be translated as endpoints and straight lines; where straight lines represent arms, legs, and the endpoints represent our hands and feet pinpointing to an end that symbolizes the endpoint. We are connected to the magnetic power of the point; where translations of movement, experiences, conversations, and music all form tangible exchanges.

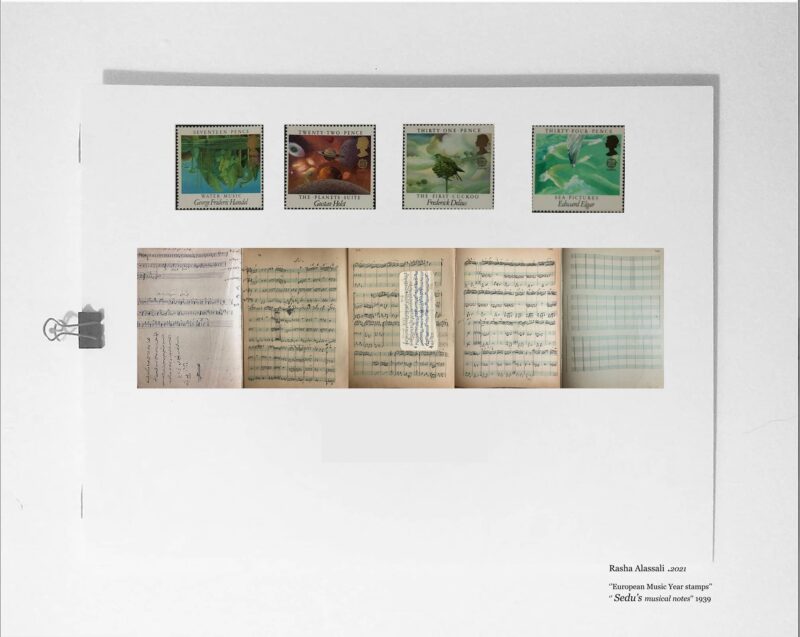

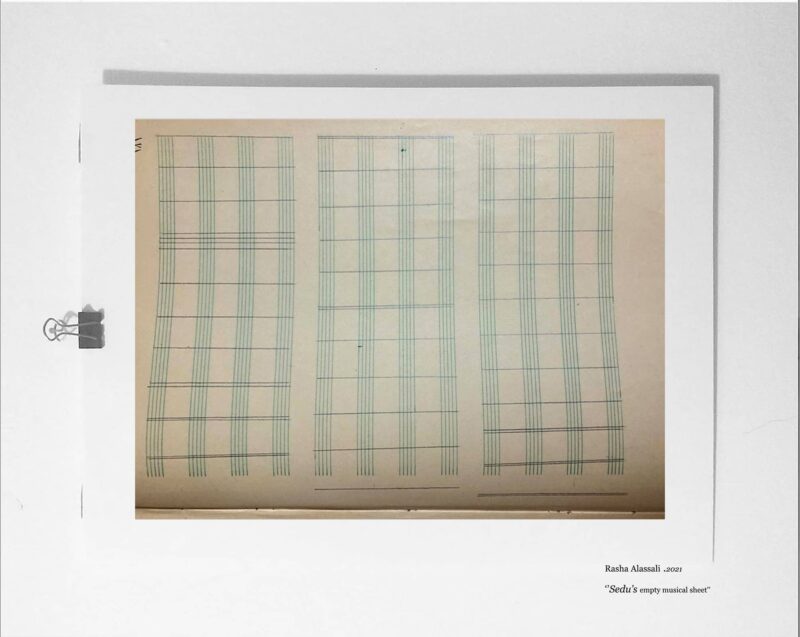

My Sedu – As we refer to our grandfathers in Palestine – grew up in an orphanage school in Jerusalem, Palestine. An orphanage that consists of a couple of rooms, hallways, classrooms, locked windows. They had strict schedules where he was only able to visit Nablus, his city, on the weekends. To seek freedom within, he studied music and later became a musician as music became his source of dreaming of inhabitation. Sedu always said ‘as musicians, we incorporeal freedom from inspiration’ – music can be a place to be inhabited and can be a form of translation of one’s emotions. Years later, during 1948, entering Jerusalem was banned to Palestinians; as a result, he had to give up his music career. Now, at 88 years old, he tells me music never left him as ‘music cannot be absent but is translated and inhabited’. At that moment, I, too, wanted to feel that emotion. I then asked Sedu to teach me music. He did so by only using his hands, as he is bedridden and unable to write. The endpoints of his hand were used to translate notes where each finger is a musical note, and the void between two fingers is another note. In doing so, he used the terms ‘circles’ and ‘points’ to explain where the fingers are considered as five black and the voids between them are four white. Moreover, the translations can be understood as the following where the thumb is a black circle (Do), the void between the thumb and index finger is a white circle (Ri), the index finger is a black circle (Mi), and so on… Describing a story into a geometrical expression can explain the desire to express one’s inner self.

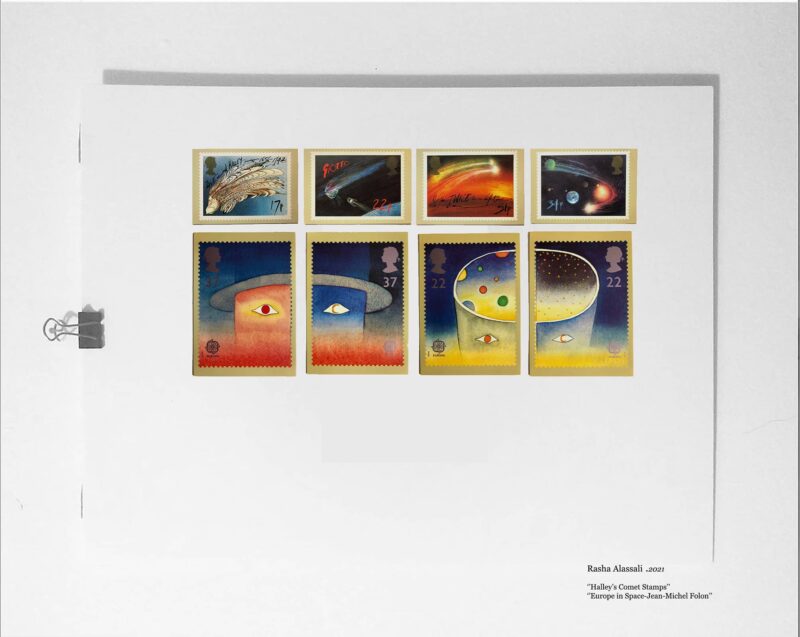

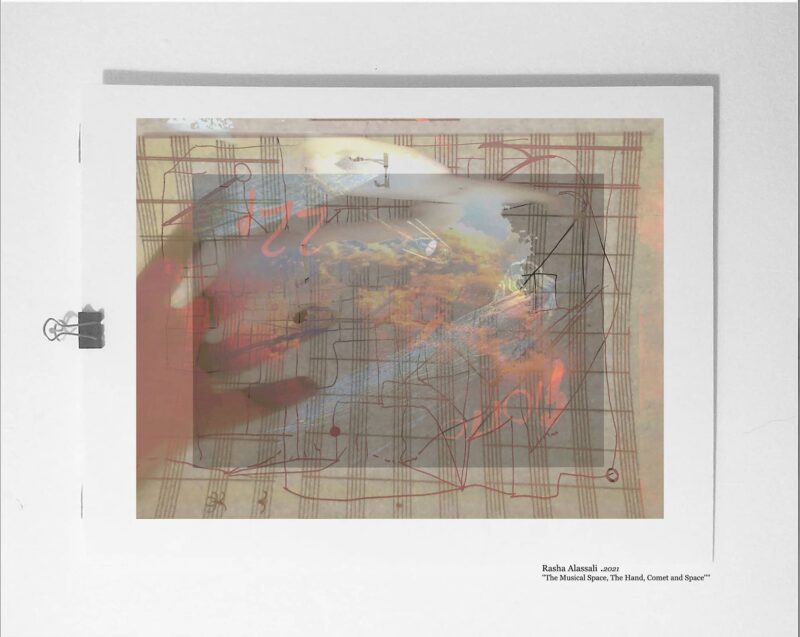

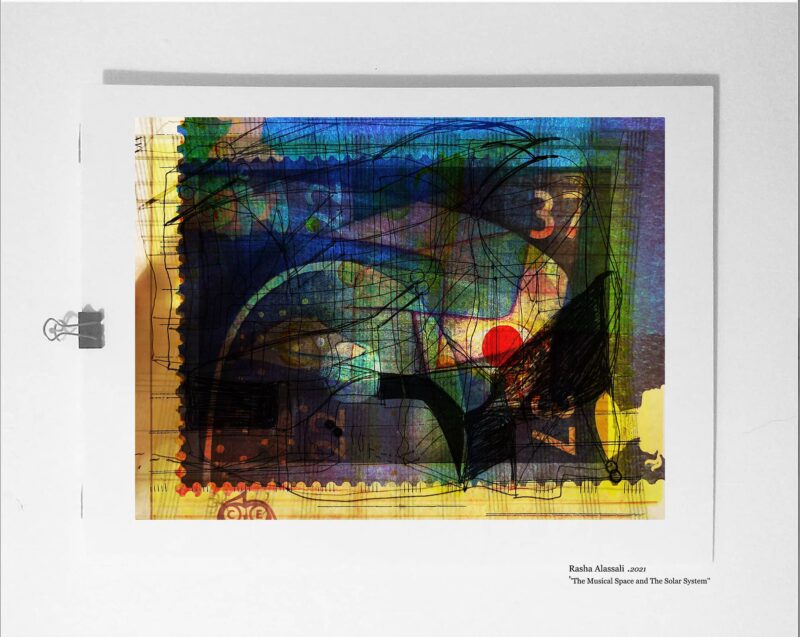

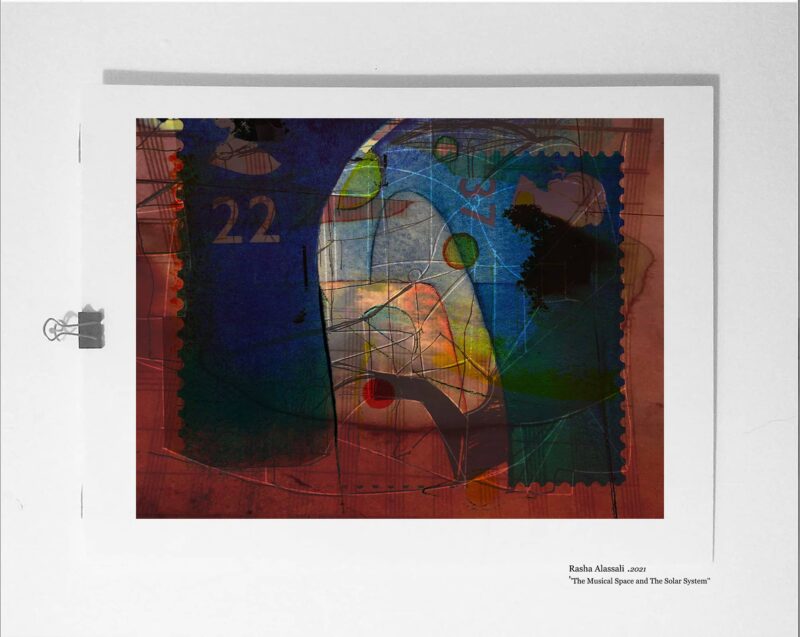

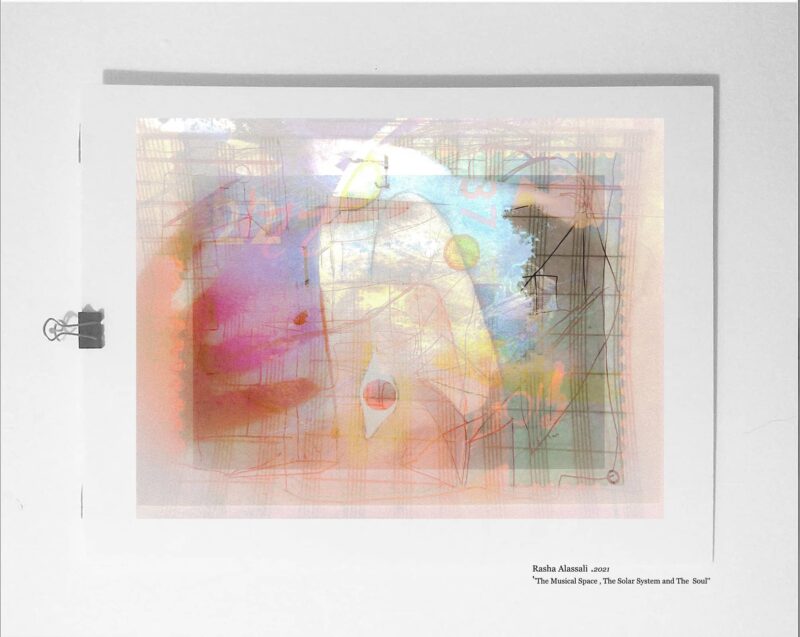

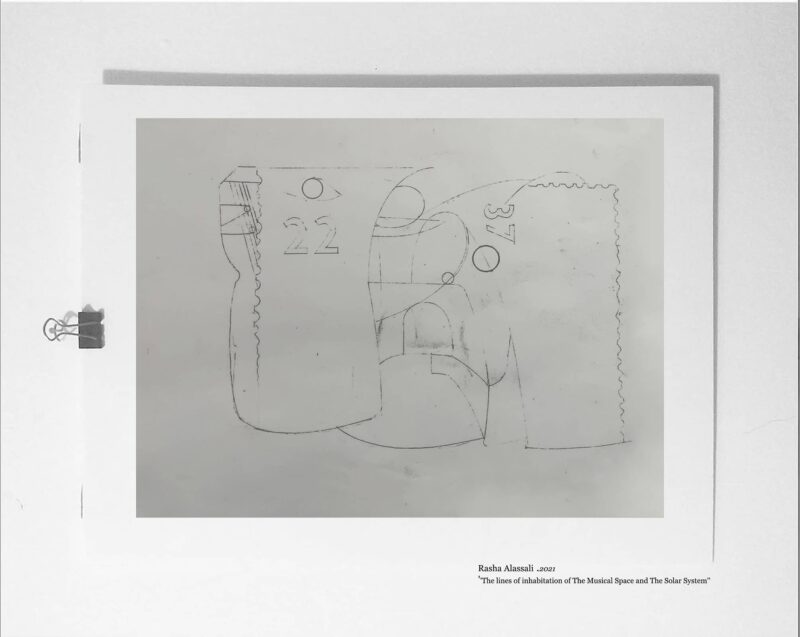

For this thesis, I attempted to understand the dream of inhabitation; whether it starts from a point, the hand, music, or the solar system as they all have a tangible connection. Coming across a few stamps collected by my dad over the years, I noticed the stamps portray images of the cosmic organization as a dream of inhabitation, where we have an eye as a sun or moon, indefinite forms, and a spatial space created by the solar system. By doing so, I used one of Sedu’s empty musical sheets as a grid, to be able to design a dream of inhabitation – no longer a dream, the sheet can be used as the main base which lines, points, and planes can be drawn. The lines and the points drawn on the sheet create their own dimension of definite spaces; and, other than drawing on the musical sheet, it can be used to be collaged with the stamps forming collages that have their own special spaces, and lines can be drawn over them to extract the actual space.

The direct relation between drawing and the hand, the endpoints of the hand, and its dynamics of movement are all used to create definite form and space precision that can be turned into architectural spaces.

In conclusion, geometries can be our inner attributes. I believe, to create, there should be an exchange with the material world and the creative mind. Architecture is described as ”appearances that are traditionally familiar, they become mute to us. We no longer react to their appeal and are surrounded by silence, so we succumb to the deadly grip of ‘practical efficiency’ the space becomes known”. My aim for this exhibition was to design spaces from inner sensations and geometries of inner attributes by starting with a story that became a memory, then turned into music – the interaction of the music with dynamics of movement, my hand drawing on the sheet, and the stamps of a cosmic organization that entitles point spaces, all are used to be able to understand architecture and create spaces accordingly.

-

drawing from life – an exploration of movement and mark making

drawing from life – an exploration of movement and mark making

as the hand moves to make visible marks, the body makes invisible marks as it moves. a dynamic

study of the physical and emotional embodiment of marks made by the same body through the

medium of movement. what does it mean for the movement and the mark that is derived from a

single body, at different times, to exist alone but next to, at the same time?film by anushka bansal

thesis advised by david gersten & homa shojaie

movement classes by somya kautia

music by kanye west -

A Thesis Was The Fate Awaiting Us Between Technologies

-

TimeTrails & ChainLinks & TimeTracks & ComeBacks

Camille Butterfield

Through the following videos and poems, I situate my work DURING SunShip in the context of what came BEFORE and AFTER.

BEFORE: TimeTracks & TimeTrails

I marked time through woven strands

Zoom interviews with faraway friends

reminding ourselves of places we love

wishing and hoping we’d see them again.Art and running on our 9-lane track

came to life when we came back

Covid-19 almost broke our stride

but we kept smiling under our masks.DURING: TimeTrails & ChainLinks

I marked time through braided strands

ten years of life passed through my hands

as I reflect on then and now

and growing up on stolen lands.Finding new homes for myself and my work

private property is a big jerk

an expansive view behind chain link

became a place for art to lurk.AFTER: TimeTracks & ComeBacks

I spend time with nearby friends

in places I love to no end

and yet some woven strands remain

as messages I need to send.Now whenever teammates run

in races, workouts, just for fun

they’ll see those joyful fabric strands

and think of everything we’ve done. -

-

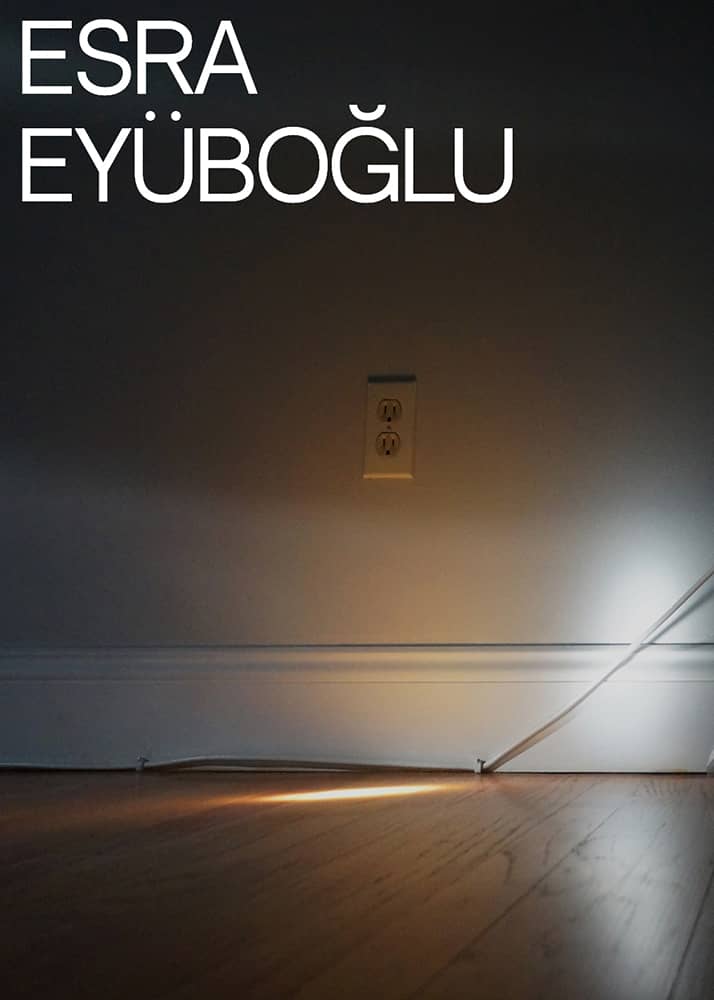

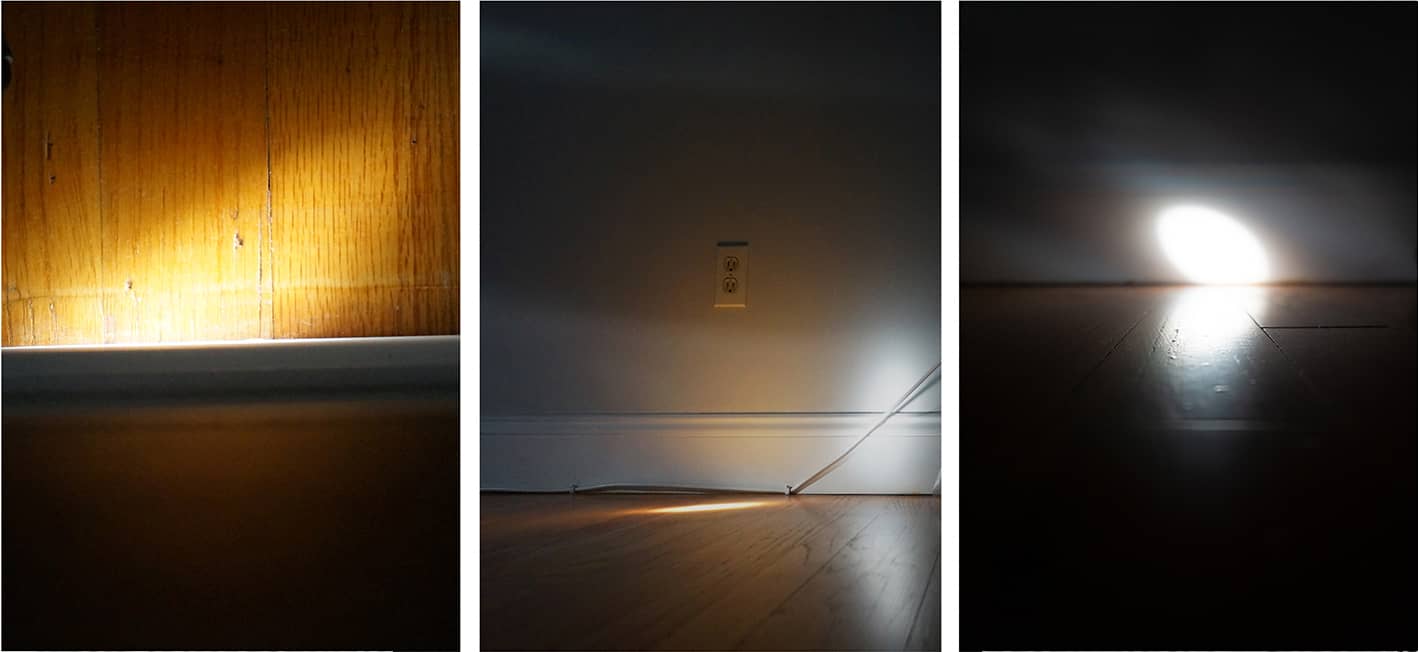

Altered Space

As an architecture student, spatial discussions have always been taking my attention. For the past recent months, I was thinking more about the light phenomena associated with this topic. That wondering led to an experiment to build up a new kind of paradigm. Taking the outside view and project to inside space with mimicking the camera obscura brings up many discussions. The technicality of it is pretty basic. The room is covered in such a way that it does not receive light, then I opened a round hole on one side. Nevertheless, the result obtained with the application of this technique makes you rethink the spatial properties.

When the connection between inside and outside is lowered by covering the windows with opaque materials, the relationship between the two spaces changes radically. I expected to see a disconnected two unattached things. In contrast to my expectations, what I encountered was very different. While I was inside, the interaction with the surrounding was nothing like what we usually experience in daily life. The outside space expanded through the inside via a small hole that welcomes the light.

Throughout the day, I have watched the figures that appeared on my walls. It felt like I was in a movie. All of the walls had a dynamic view on them. The room wasn’t the same ordinary one anymore. While I was watching and experiencing it, I kept hearing the sounds from nearby; tree pruner, people talking, birds chirping, train passing by… All these combined in a way that complemented each other.

After my observations were over, I removed the arrangement and made it as it was before. It was the same room, but mysteriously it was nothing like it.

-

My Heart is a Lonely Hunter (mixed media 2021) text as poem October 2021

A vintage

French

linen

gar-

ment,

worn by

person

unknown,

bought off

the street

in time of

pandemic

and a

length of citrus,

sunny net,

tissus en filet

from

the dust

of a stall

near where

Vincent

lived with

Theo.A hanger,

found, and

wrapped

around

with gilded

straw,

a tangled

line

and

thread,

and

Japan-

ese

fish

hook,

to

secure

this hanging

heart

hugging

a brown

paper

bag, last

winter filled

with

oranges,

and now

a room

for Paris air

gulped from

the window

in my chambre

de bonne,

in the eaves of

the 15 eme,

where I was

confined,And inside this,

a fragment of a

tree

which had

sprouted

from a

root which

Van Gogh

painted

last.This I gathered

in autumn

Auvers-

sur-Oise,

with the

small

white

feather

lying there,

and

bedded

them with

leaves

which smelt

of auberge

tobacco,

the leaf veins

still

coursing.all this

wrapped

around

with

golden

thread.This bounty

fast with

golden

thread,

heartened

and

suspended,

from a

picture

hook,

above

my

lit

in

my

darkened

chambre

just

as the

light

cord

which

hung

over

my

child

hood

bed.

beat

out

the

night

with

its

sound

less

tick.

Christine Finn b Jersey, Channel Islands 1959

Mixed media: wood, gold thread, feather, leaves, brown paper, gilded raffia, tissu en filet, net, metal hanger, Japanese bronze fishing hook.

My Heart is a Lonely Hunter is a work which has been incubating for a number of years. This is a long background; the briefer and more immediate, is the poem which also accompanies the work.

The piece has its origins in my fishing heritage, and searching for lead weights with my father, which would be tangled up with fishing line on the groynes of a pebble beach in east Kent, England. It was his home, but not mine. My mother and I were born in Jersey, Channel Islands, so closer to France. We moved to Deal, Kent, in the autumn of 1967. The sand beach and island vistas changed to the English Channel and French cliffs glimpsed in good light, almost as close as Jersey. My father had Parkinson’s and so fishing, and all the outdoor activities he loved, were denied him in his later years. He died in 2004, my mother less than a year later. I inherited the house in Deal, which was also an incubation of war damage, not that I could see it. I moved from Rome to rescue the house, made it into an installation for living in supported by RIBA and Arts Council England in six public works between 2007 – 2013. The first four online at Leave Home Stay. www.leavehomestay.com

But my bliss was also walking the nearby bay, looking for fishing line which I used as “paint”. The blues, and greens, and oranges became installations in the garden, which had been flooded by the Channel, in the 1970s, when I was away from Deal at journalism college.

That melding of sea and land came through in the material of the house, as the salt leached into the plaster. I thought it was beautiful. But after the 2008 financial crash such poetic sensibility was buried in the practical. How to keep a house which was my home and studio, workspace and catharsis? In 2012 my entire house contents went into storage on promise of a sale. Yet another red herring.

Then the empty house held a new dynamic. White space. I borrowed works from the art therapy unit, Valetudo, at St Remy de Provence, where Van Gogh lived and worked. Lavender from there was worked into the floorboards by visitors while they listened to Van Gogh’s letters to his brother, voiced by an actor friend, Michael Maloney. I had workshops on the theme of the overlooked – Harold Chapman’s Paris photographs from the Beat Hotel. I invited two artists from the disability arts platform, Outside In, then based at Pallant House iGallery in Sussex, Ian Sherman and Elzbieta Harbord, to occupy two rooms as galleries. One evening, the music of Nick Drake’s Pink Moon played on his family’s old gramophone, in my parents’ old bedroom, the original cover painting propped on the mantelpiece. An alchemy performed by Cally Calloman.

After six installations, supported by Arts Council England, a crack in this creativity. Fighting foreclosure in the wake of the crash, the house was sold thanks to a serendipity involving my reporting hero Alan Whicker and the London agent he knew, Roy Brooks. Both passed on, but oddly present just in time.

I walked away with five bags, and my heritage in storage in Deal. It is still there, gathering momentum; I still believe in it as an artwork. Just before the pandemic, I performed The Container Project. I invited archaeologists from the Museum of London to dig a test trench into my hidden chattels, while I wrote what came to mind seated at a desk in a separate shipping container. I produced 60,000 words, the archaeologists photographed hundreds of artifacts. I worked behind thick plastic which hinted at presence and absence, as lights came on and off over two weeks. Neither of us communicated so when a few artifacts were publicly revealed weeks later, origin stories were at odds, just as I anticipated. I planned then to view the hundreds of image files as far away from Deal as I could imagine that was new to me. Patagonia. This also a nod to Bruce Chatwin, and his fondness for artifacts and stories..

And then the pandemic and so everything still. By chance I have ended up in Paris, to continue my experiential investigation of artists living in extremis. Since August 2020, home has been a tiny chambre de bonne, a single room in the eaves, familiar in the Haussman-era buildings of Paris. My first was in the 6 eme, now the 15 eme, where I can see the arc of the Eiffel Tower beam passing in the sky. This time is challenging but fruitful and sustaining. My technology failures are mitigated by daily walks and bus journeys with my Leica, its leather case concealing my only digital concession, save a laptop. I have no smart phone; I am constantly gathering in an old school way.

For this SunShip project I wanted to channel the Mexican Surrealist, Remedios Varo, and her vivid orange rich painting of women embroidering the cloth of heaven, which I first saw in Mexico city in 1995. I repurposed that image for Lead to Air, a continuous writing work I performed in the barn at Arts. Letters and Numbers on presidential inauguration weekend, 2017. Like the text which emerged as I sat with my chattels in storage, I have yet to read the six hours of typing I produced.

But back to My Heart is a Lonely Hunter, and the title from Carson McCullers’ 1940 novel about outsider-ness. The Heart is a Lovely Hunter, which came into my mind when I made the work in my chambre. The piece I made was the culmination of weeks of longing and dashed expectations; ideas in my mind which could not be realised had to be corralled. I thought to send a wash of silk out of my window, an expression of freedom, to be documented by neighbours. It was inspired by a long-held interest in the Mexican Surrealist, Remidios Varo, notably her work Embroidering the Earth’s Mantle, which had also inspired Lead to Air, my performance piece at Arts, Letters and Numbers in 2017, kindly enabled by David Gersten, who also photographed the performance.

When that proved impossible, I chanced on some lengths of net – tissus en filet – in a store in the 18th. Vibrant orange and yellow, it spoke to me and the blaze of the SunShip. I bought what there was. Sensing something, I travelled north to Van Gogh’s resting place in Auvers-sur-Oise. I thought to see what his grave might share, but before reaching it, rejected the idea of taking anything. Instead, close by his last home in the Auberge Ravoux, I came to the place which had inspired his last painting, of a tangle of tree roots, identified during the pandemic, and now fenced off, leaving holes through switch to peer at the trees which had grown from the root over time. On the road, under its autumnal canopy, I foraged for leaves and bark from that tree. Those fragments, and a white feather which happened there as I looked, are contained inside My Heart is a Lonely Hunter, at its very centre.

In my chambre, I wrapped the bundle of wooden fragments, leaves and feather in gold thread. I placed the bundle in a brown paper bag still scented with the oranges it one contained, harbingers of brighter days. The bag took a gulp of Paris air as I tied it with more gold thread. I began to wind the net, trapping, or embracing, the wood and the air, with the memory of flood water, and the fire passion drives art. As I wrapped, I played the recording of A Lot of Sorrow, a collaboration between the artist Ragnar Kjartansson and the American band, The National, to which I listened while performing Lead to Air.

As I began to wind the net…trapping, or embracing, the wood and the air, with the memory of flood water, and the fire which drives art. I held it fast with bronze Japanese fishing hooks. The shape morphed from the sun into that of a heart. That evening I suspended it in the window seven storeys up, over the rooftops of Paris. It hung there passively, but did not speak, even as starlings chattered in a tree below. When I brought it inside it began a dialogue with a rough linen vintage dress, worn, stained, and possibly from an institution. It has spoken to me from the street at the Cligancourt flea market, and lay silently next to my bed during lockdown. I hung over my bed… the two met, and the work at last seemed complete. The heart is contained in its elements. The heart of my own life is still trapped in the container, held fast for almost a decade, a tangle of stories.

One day I will travel to Patagonia, and continue to tease out the threads.

Photos show detail from Leave Home Stay, a site specific installation in my then family home in Deal, England, 2007, originally commissioned by RIBA and all funded by Arts Council England.

Flame Tree, an install using found fishing line from the beach at Deal and Sandwich Bay, Kent, UK

My Father’s Lines, an install inspired by what I found in my late father’s shed, and line found where he liked to fish off Deal beach.

My Heart is a Lonely Hunter, site specific install at my home in Paris, 2021

-

The Mass Individual

Patrick Cheng-Chun HWANG

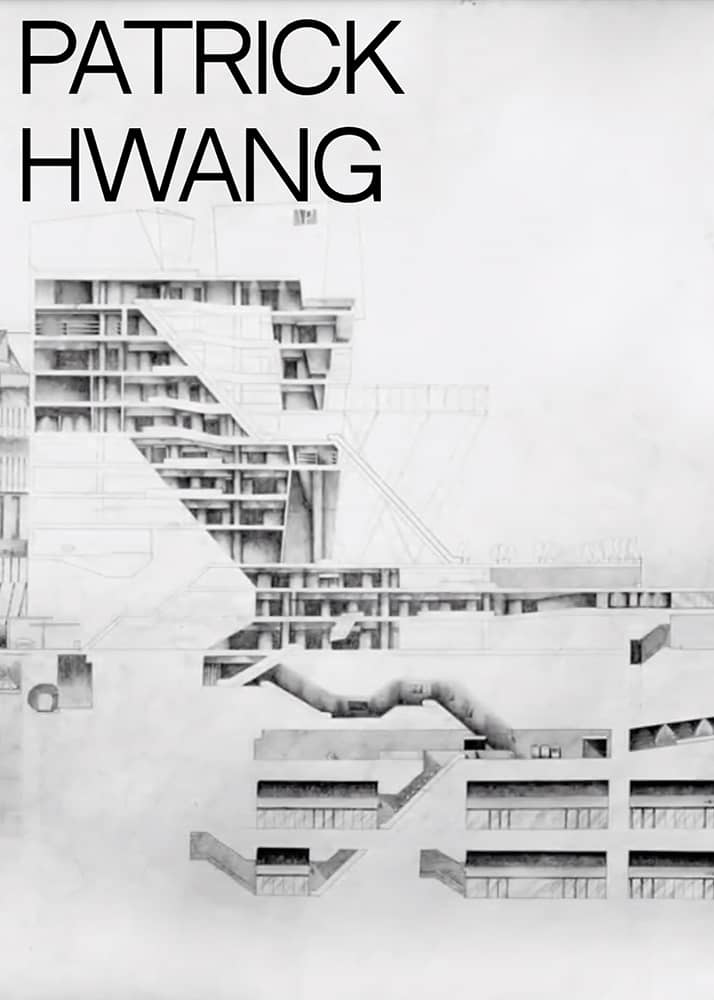

Bruno Latour has coupled drawing and thinking as not only an embodied experience but gives credence to its ability to enhance comprehension and trigger imagination. Others have argued for drawing’s capacity to stimulate synthetic feedback between the haptic and the cognitive perception; as well as our ability to understand the world. Including research and experiments in the fields of the fine arts (Alpers 1983), architecture (Frascari 2011) and psychology (Arnheim 1974). This understanding of the potent nature of drawing and its positive effects underpins the starting point of this work. There is, however, one question that remains unanswered. In exploring the synergetic and mutable potential that drawing creates, this project is interested in what goes beyond the individual, and toward its impact on the collective. If drawing can arouse a productive symbiosis between the mind and the body within an individual, what happens when the action of drawing is expanded to involve two, five, ten, or even twenty collaborators? What kind of visual, cognitive, and social interaction will this action-led togetherness ignite? On a hot and sweaty summer in 2021, a group of twenty students (plus friends) at the Chinese University of Hong Kong began to find out.

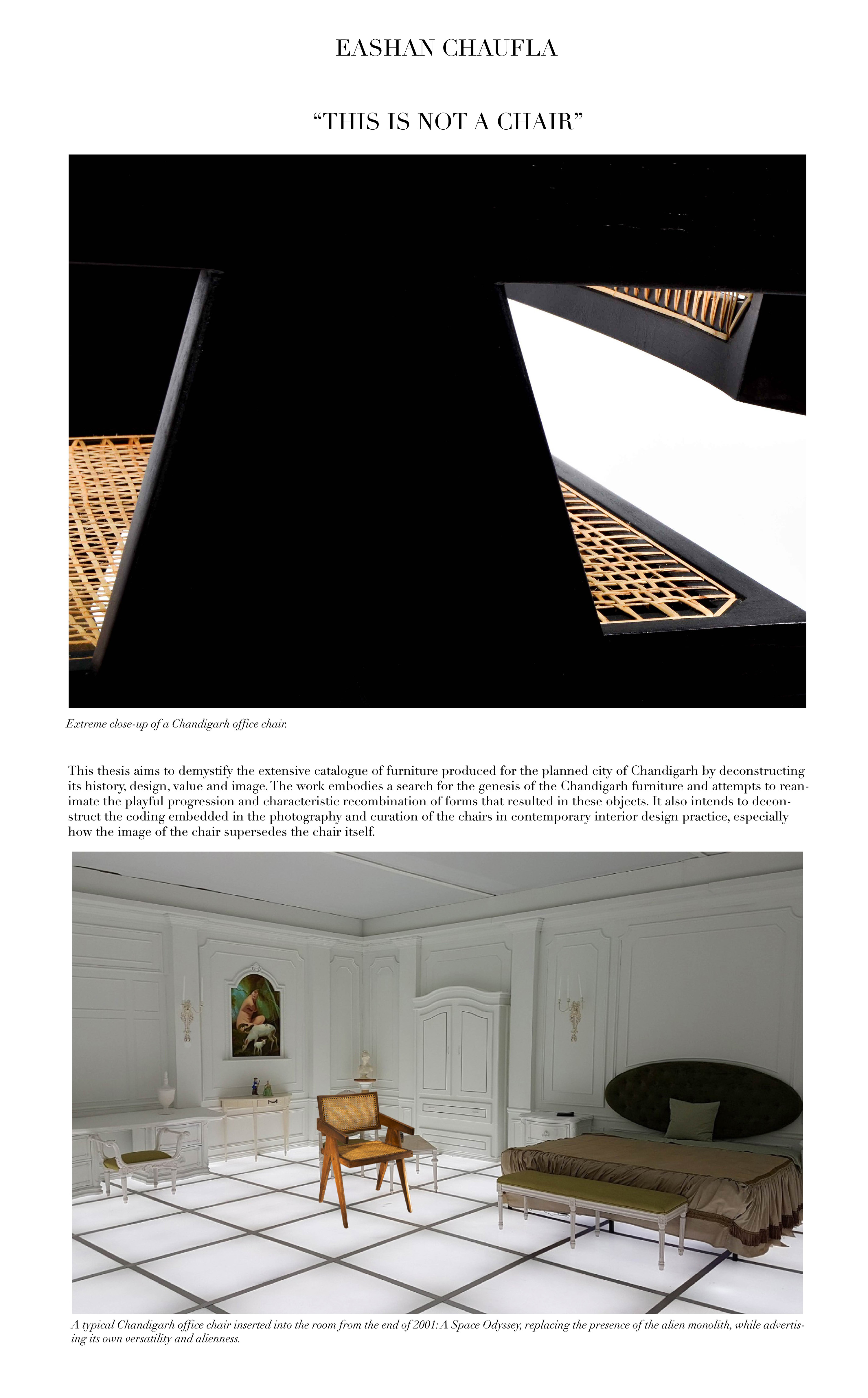

“The Mass Individual” is a two-meters by ten-meters long drawing drawn in graphite across an intensive four days time frame. The MTR Stations (Mass Transit Railway), an important economic, social, and spatial construct for the Hong Kong people, serves as the common link between the students. It was a means to explore the question of the masses and the individual.

Credits:

Lincoln CHAN, Nok Yue CHAN, Tin Yuet CHAU, Sien Yi Cindy CHENG, Hoi Lan CHEUNG, Ming Chung Andi CHEUNG, Yi CHEUNG, Lai Sum Julie FONG, Ho Nam LEE, Hiu Sun LEUNG, Lok Yiu Vonnie LEUNG, Truman LEUNG, Alex Kelvin LI, , Charmaine LIN, Ting Fung Winson MAN, Wing Yi SO, Prudence WAI, Chuyu XIONG, Tin Ho Michael YEUNG -

Changing and Unchanging Things

My Narrative

The act of observation has been the primary source of my interests and the leading force in shaping my way of living. From an early age wandering around, moving through space, and experiencing it from the eyes of a flâneur fascinated me. While engaged in the exploration phase, sketching, representing, documenting, and analysing were my main focuses which enabled me to take inspiration from the whole observation process. Each tool I experimented with while working on, revealed a new path for me. I needed a space, the space needed time, and the time needed moving figures for me to comprehend my surroundings. The more I found myself intrigued by the idea of an instance of space, I grew closer to questioning it, therefore I studied architecture in my undergraduate education.

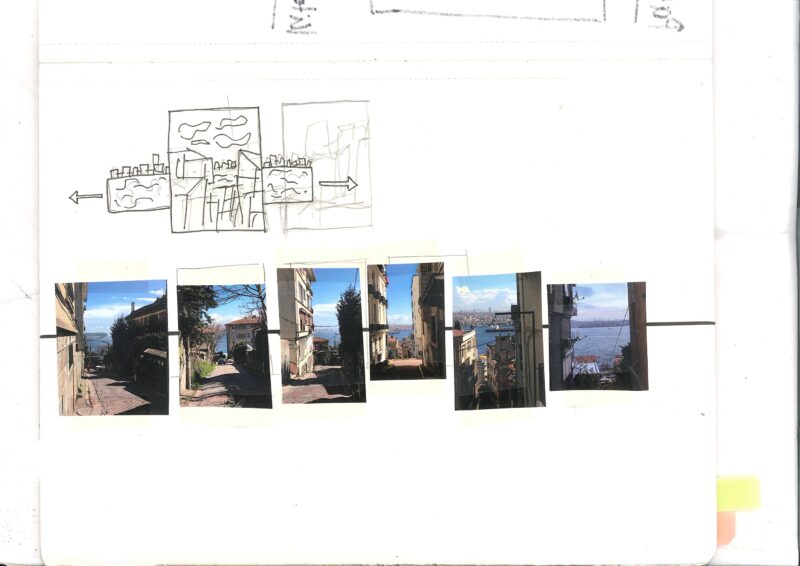

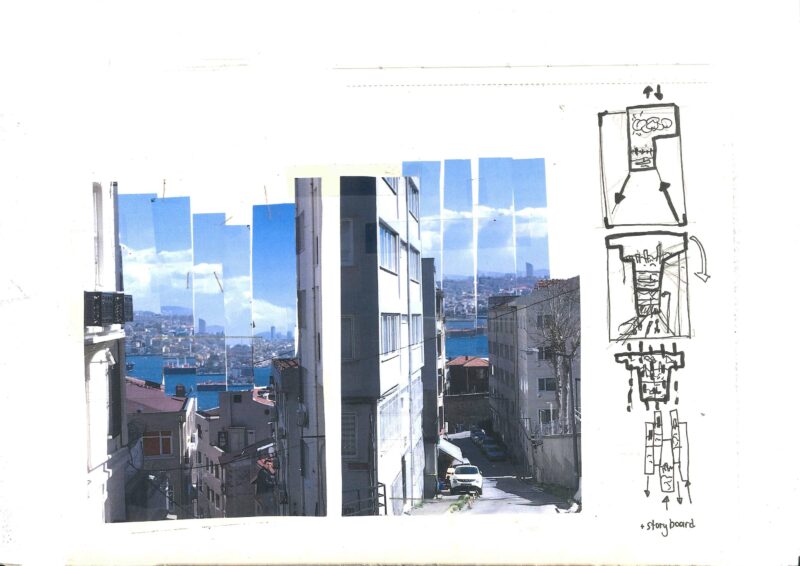

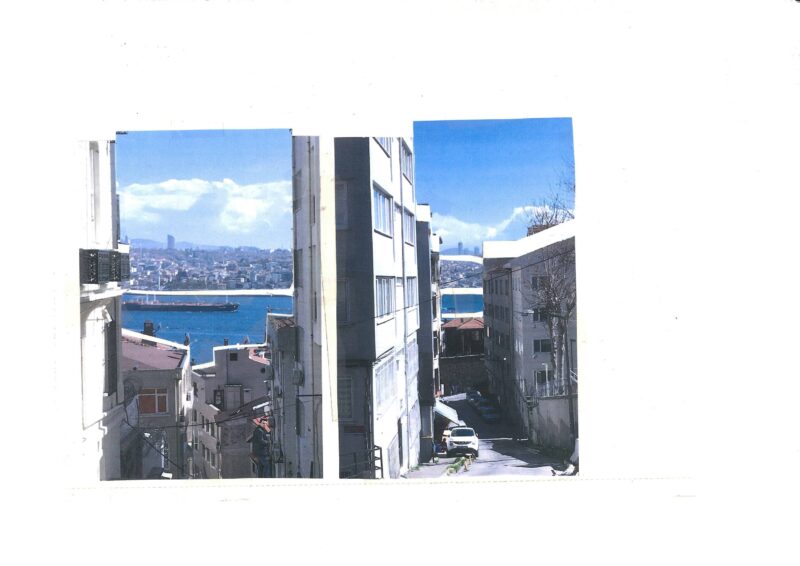

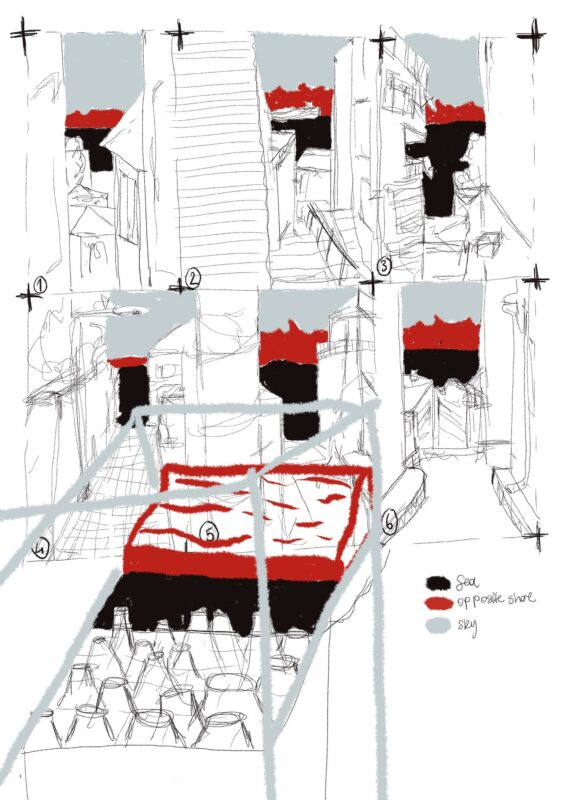

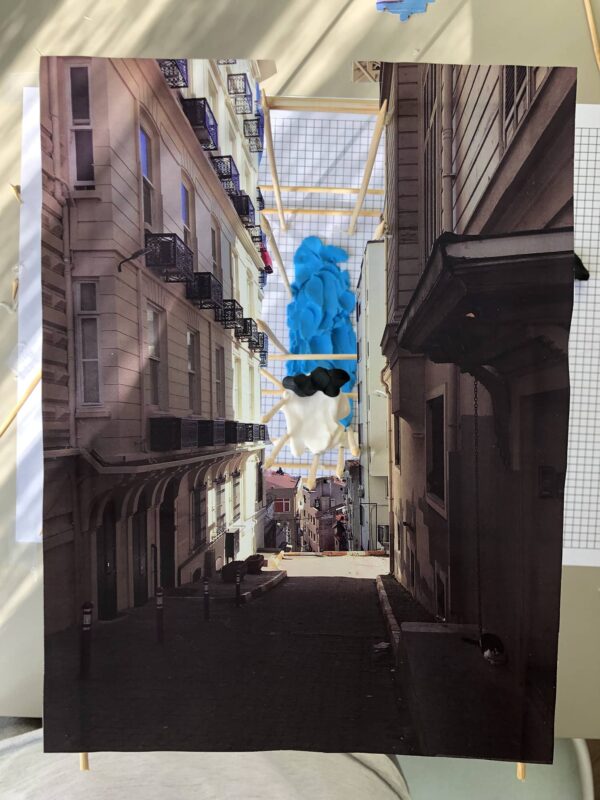

Almost 5 years ago, when I was walking in Istanbul, I found the place where I belong. This place name is Gümüşsuyu near Taksim. I have a connection with this place so almost every week I visit and all of my visitings like my devotion. Every street has the same layers [ sea, opposite share, and sky]. It is creating harmony. I analyzed their proportions and their changes. This changeability is connected with scales, elevations, and station points. All of them created my different focal point and stillness and motion that links to the mystery of life. We can think, the focal point is a subject, station point is a writer.

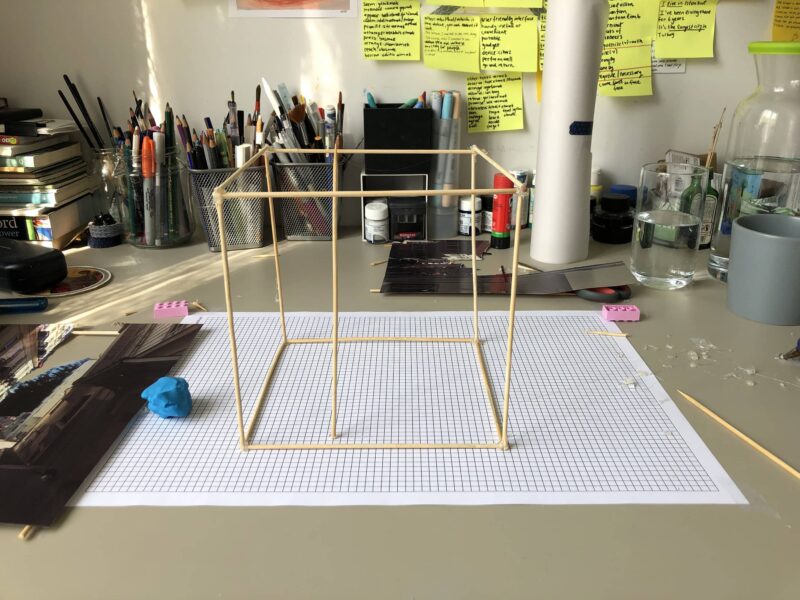

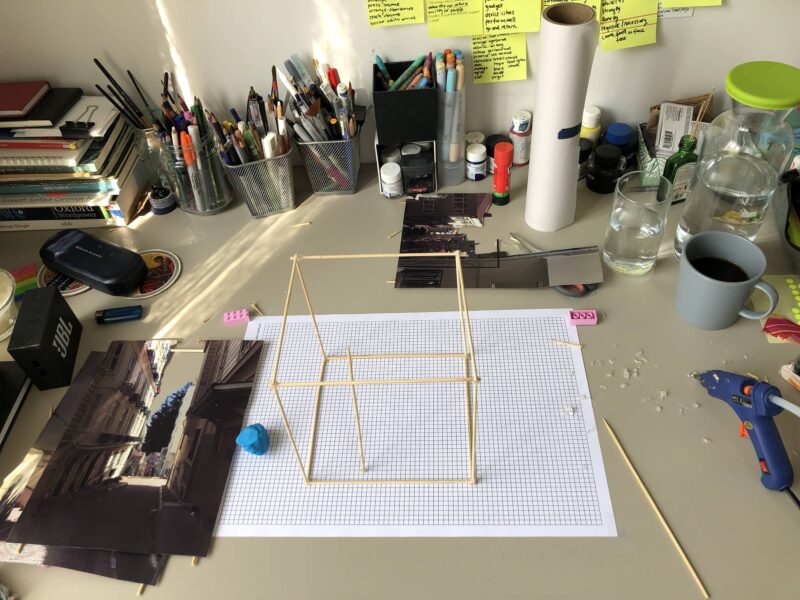

My Experience

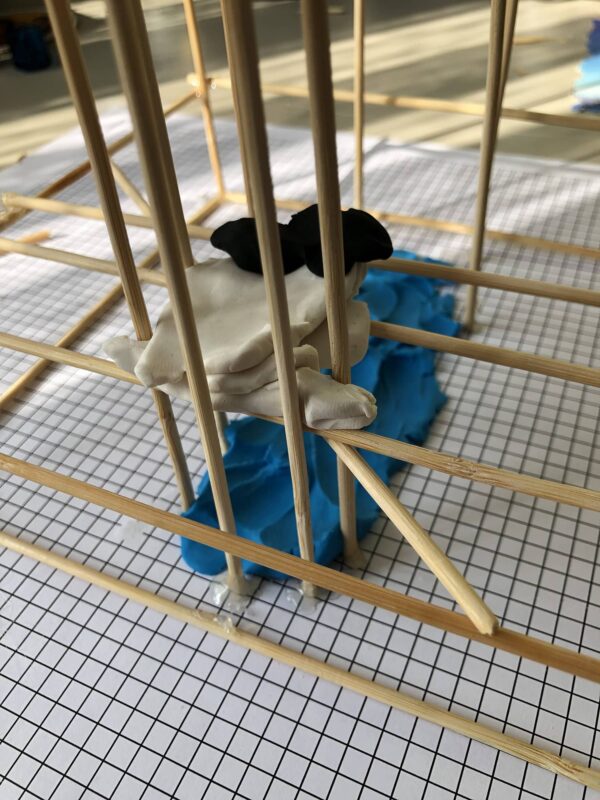

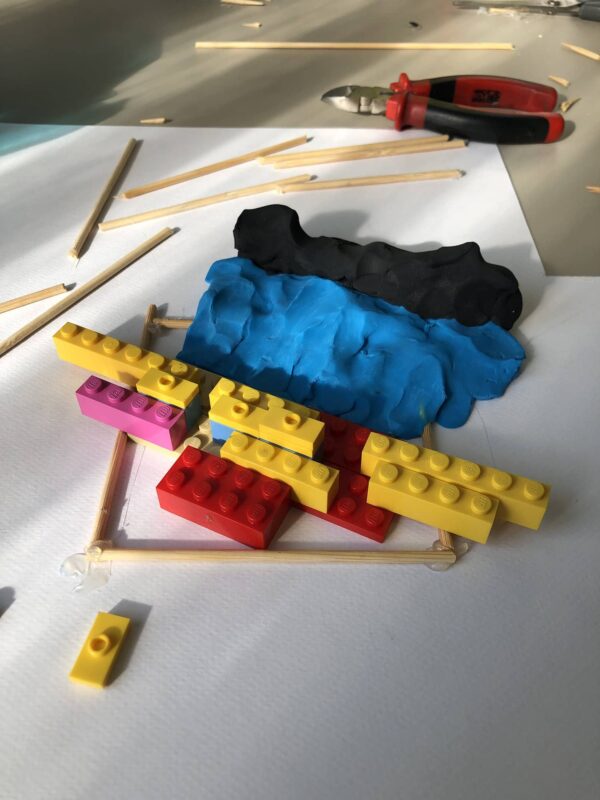

I tried to understand the relationship between my photographs and my observations. Making a storyboard is searching for a story. Also, topography affects all these factors so I designed my route’s box for a sense of depth. All of them start to relate with my observations so I think, Should I design a storyboard about my observations or my storyboard be a way of searching for a story with crafting, space, drawing, photographs, models [2D, 3D]. After I decided, my way of making a storyboard is searching a story, and crafting became part of my animation that includes my layers’ depth because incorporating feeling and experience into the animation is quite significant for my selection. I used many different materials to achieve this [stick, printout, modeling clay, lego] and especially a grid system with reference points. My model gets an abstraction about my focal points. Finally, I created my own experimental spaces with all of them and I started making my first stop motion animation with my frame by frame method.

Experimental Stop-Motion Animation Brief

I have been visiting the place for 5 years and I can say, nothing changed but every day I changed. The meaning of Gümüşsuyu has changed for my soul with each visit. Experience relates to how I see what I’m looking at.

-

worlds between worlds

About the work

Underwater photo & video – Monica Lacey 2021

Images captured on unceded Mi’kmaq territory, Epekwitk

(Prince Edward Island, Canada)Explorations of vision, of spaces never before opened, new frames of reference, flip the plane. Views of the changing space while we, too, are changing. Forever now. Time becomes viscous, circulates and we’ve never known such tenderness. You can be visible or no – you choose – but you are the bridge either way. A pause between great breaths, make your wish. A good space. A world between worlds, all the ancient traces. The Sun becomes the heart, the river freezes, we all made the same wish: to be braver. Be with it, the intensified attention, show up. Show up. Equalize the pressure, until it opens, the mystery, jammed thick with beauty.

About the artist

Monica Lacey is a multidisciplinary artist driven by curiosity, service, and the pursuit of beauty in all its forms. She is deeply inspired by nature and by liminal spaces. She prioritizes connection and communication in her practice and employs a variety of tools as needed to express the vision of each project, from underwater photography to encaustic to watercolour.

Monica holds a Diploma in Textiles and Photography from the New Brunswick College of Craft and Design, and has received several awards and grants for excellence in her work and service to her community. She has attended residencies in Canada and the US and her artwork is in public and private collections across North America.

She lives in Charlottetown, PEI, Canada on unceded Mi’kmaq territory with her husband and daughter, where, in addition to her visual art practice, she writes, plays the piano, throws dance parties, and teaches Kundalini Yoga and meditation.

-

The End of the World is Forever (2:35)

Directed by Weihui Lu

Curated by April Zhu

Produced by Brooke JensenIn my practice, I deconstruct elements of traditional Chinese landscape painting to examine themes of immigrant identity, environmental issues, and mental health. Monochromatic landscapes, painted and printed on translucent materials, become both an attempt to reclaim an ancestral past, and an expression of grief at what our relationships to the land, and ourselves, have become.

This installation draws from the imagery in Xu Daoning’s Song dynasty painting, Fishing in a Mountain Stream, which depicts the barren sides of a mountain range. By using this historical record of deforestation and recreating it as a linocut print, I attempt to change the scale of time in the larger conversation about environmental concerns, from a reactionary search for quick stop-gap solutions, to the need for more long-term paradigm shifts about human-land relations.

At the same time, the stark palette and abstract marks which obscure and degrade the image also speak to an interior existence, and the emotional toll of living in a time of perpetual crisis; it remarks on the damaging capitalistic tempo that is as much a strain on the human psyche as it is on the environment. The continuous handscroll format of the piece acts as a resistance to the speed of modern-day art consumption, in hopes of re-establishing an embodied pace in the viewer’s perception of the work.

I hope that despite the heaviness of the content it grapples with, this work can still communicate some sense of solace. The title, and repetition of the central image, are a reminder that humanity has encountered many moments of near apocalypse before – and that perhaps we are only in one stage of the ongoing cycle. -

A Mythological Journey

Flood

Every once in a while there is a flood and Mesopotamians wonder why their life and everything they’ve built was destroyed by angry gods. In Semitic languages, the word for civilization is taken from the word for Life. The one who crafted the Ark that saved life as well as the craftsmen who made their world habitable, was given eternal life. He is living on an island in the middle of the sea of death, where the sun rises. Gilgamesh, the hero of the very first piece of literature, eventually finds out that he would not be given eternal life. Instead he diverts the river and builds his tomb right in the bed of it in a way that it would last forever. After his death, the river is diverted back to its main course over him. Gilgamesh is eternal. Is not the epic of Gilgamesh an eternal story as well?

Covenant

Gilgamesh can only take over nature with his friend Enkidu. Neither of them can make it individually. Shamash (the Sun God), who is the God of all covenants, supports them. The friends in their journey come to a scene denouncing Ishtar, the Goddess of fertility. Was the choice of Shamash over Ishtar a diversion that foreshadowed the history of civilization right at the beginning? Were not all the heroes supposed to be fighting for life instead of fighting against the other?

Tree

Mashi and Mashianeh, the original human beings in Iranian mythology, are two plants. Their descendants, the talking trees Arenawaka and Sanghawaka, turn out to be sisters of Jamshid in the Shahnameh as Arenavaz and Shahrnaz. Captured by Zahak, a three-headed dragon, they are freed by Fereydoun after one thousand years. Though they were mostly silent in the Shahnameh, they later become the storytellers Shahrzad and Donyazad of Hezar Afsan, and transform the evil king Shahryar into a good king after one thousand and one nights. The talking tree, as one of the seven styles of Persian art, has not been woven on carpets for about a century now. Is a new story to be woven?

Paradise

Persian architecture begins with the idea of paradise: a walled garden in the middle of desert. The courtyard is a garden with water at its center, brought by aqua-ducts from up to a hundred kilometers away. Shabestan was a garden of trees. The sky was a dome of blue stone. Shamseh was the sun at the center of the dome. The Persian carpet was a garden spread inside. The skin of architecture was tattooed with floral patterns mingled with voices written as words. Is the paradise lost?

Fall

The hero is supposed to defend life against destructive evils. There has been a gradual descent of the hero through history from Gilgamesh to our present day villains. Chal Meydoun, one of the five neighbourhoods of Old Tehran, which was the neighbourhood of لوطی (luties), who considered themselves the heirs (descendents?) of ancient heroes, is emptied out of life. The dried up underground aqua-ducts of Tehran are a paradise for homeless drug addicts. What do grave-sleepers rise every morning for? Is there a descent from sacred prostitution to selling the body for food?

City

Tehran has been an underground city now for more than four decades. Life has receded from the city to its interiors. The public sphere is gone. The city is decaying. Corruption is the norm. The old neighbourhoods of Tehran are devoid of life. Losing the public sphere, the society is lost as well. The city is populated with individuals living just next to each other, only sharing a geographical border. To reclaim the public sphere, making a collective discourse is a necessity. At the same time, to make a collective discourse, the public sphere is a necessity. How can the vicious cycle be broken? Is it possible to build up a collective voice in an underground labyrinth? Would writing a new story make it possible to reclaim the public sphere? -

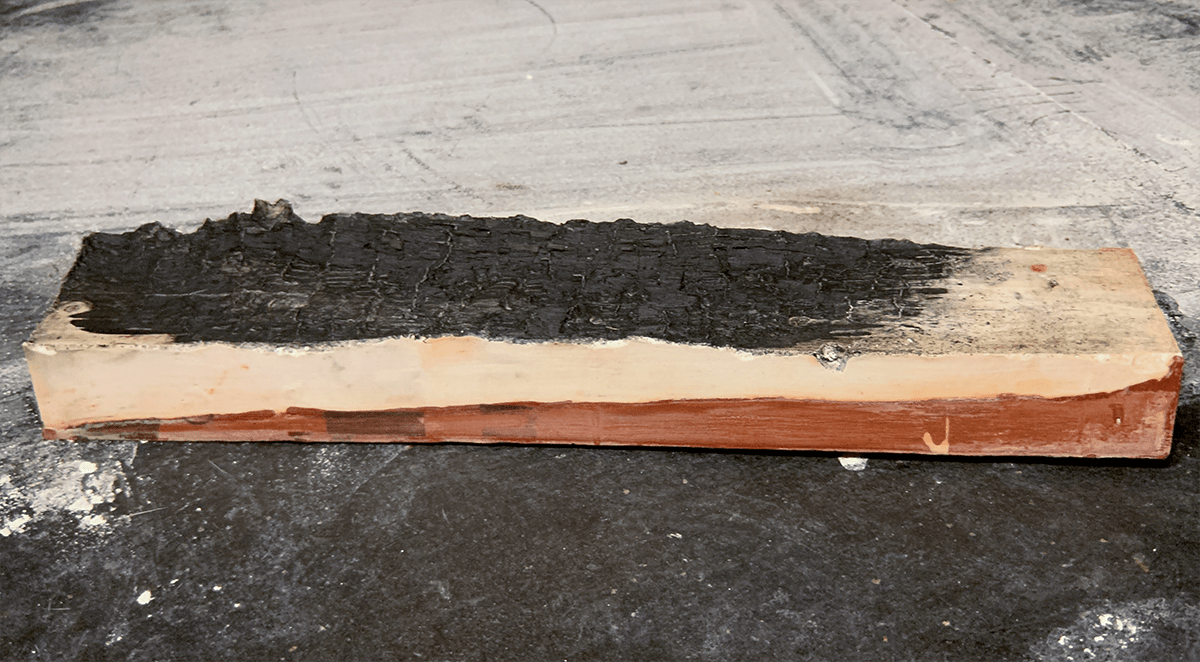

“In a certain sense interpretation probably is re-creation . . . [the created work] has to be brought to representation in accord with the meaning the interpreter finds in it.” – Hans Georg-Gadamer, Truth and Method

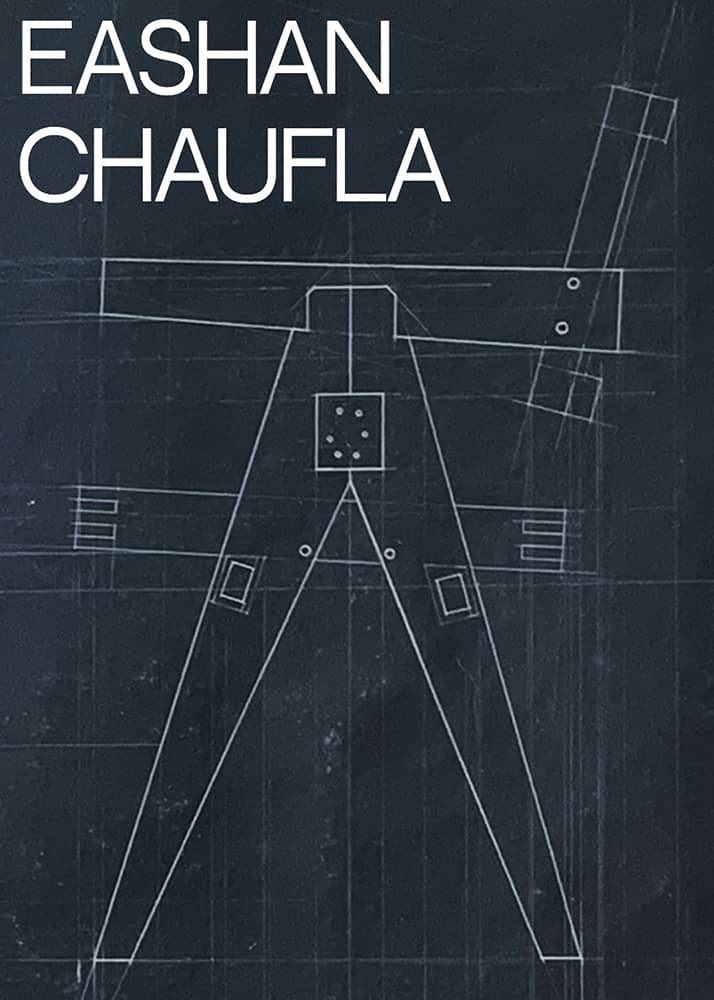

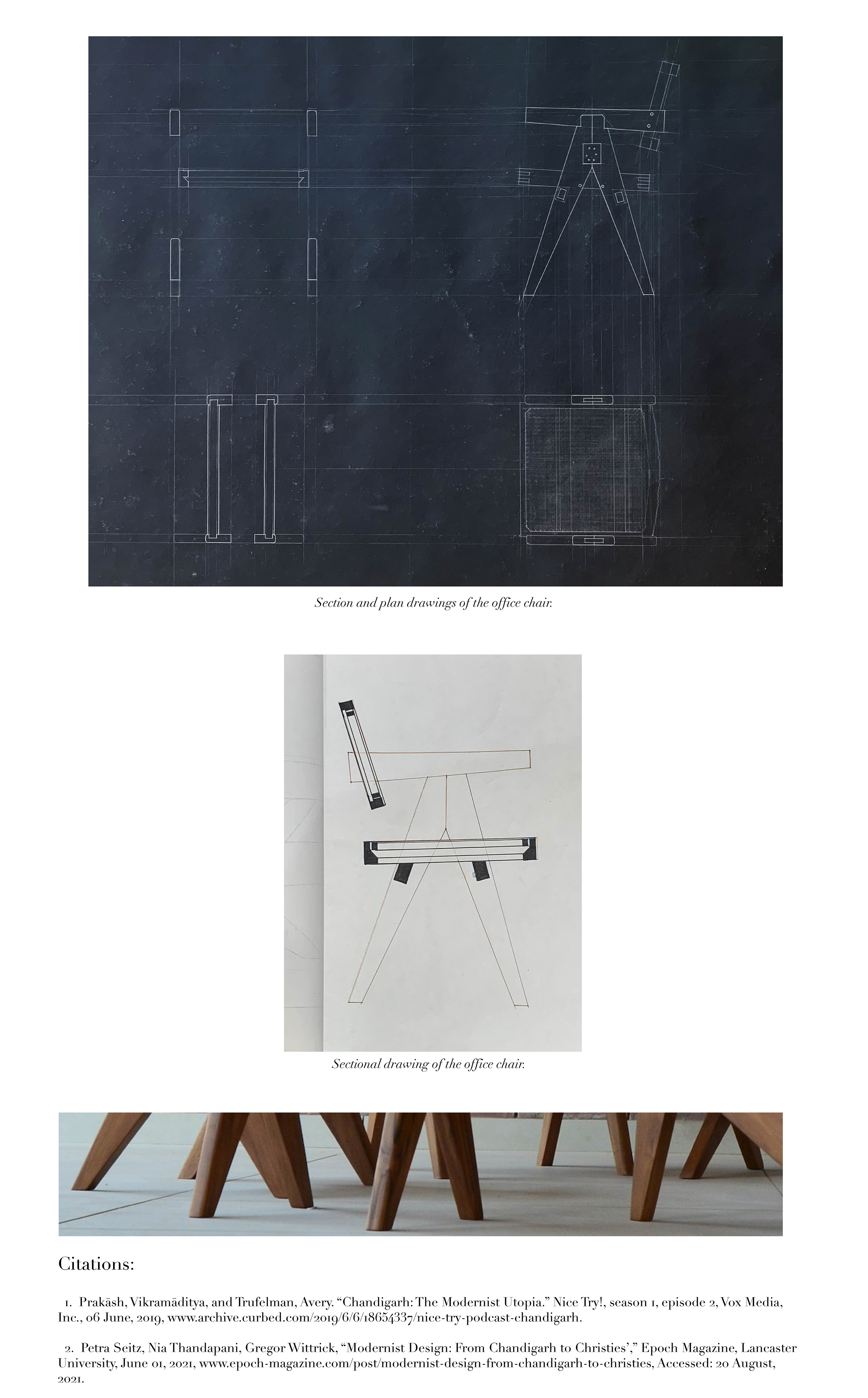

My work as a furniture designer is primarily interpretive; the world I inhabit is a kind of created work that I am constantly recreating through interpretation.

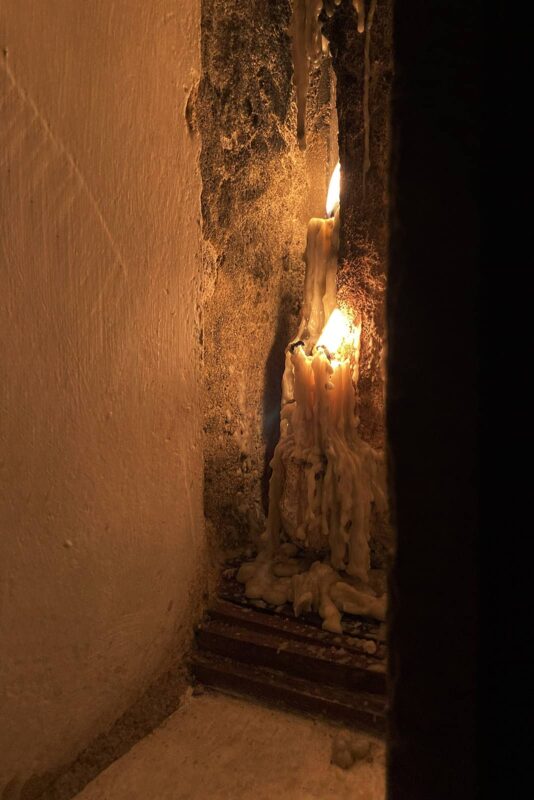

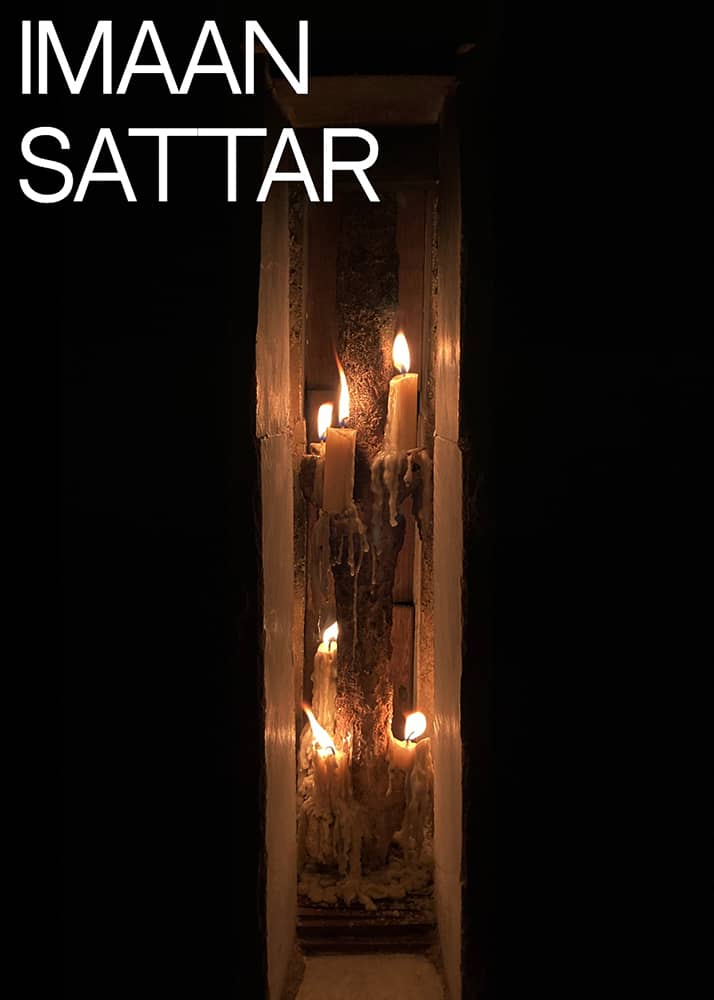

The first in a series of site-specific objects, The Sea Breeze Candelabra is my response to modernity. It works with a manually rotating exterior shell which functions to protect the candle flame within from the natural force of the winds. The large, all encompassing sea breeze versus the striking but delicate candle flame turned out to be a very interesting dynamic. You can find a video of this in use in the photo gallery above.

Born and raised in Karachi, moving back home catalyzed a deep engagement with the modern, urban city, which I’ve come to realize, has very complex socio-historical circumstances. Modern life, especially in a congested city, is very claustrophobic. Finding the right space to work through my questions was the first order of business, so I set up shop on my roof where I found sea breeze and room to let my senses finally stretch out and relax. I needed uninterrupted access to the environment I was interpreting.

Recently my grandmother mentioned that not too long ago you could feel the sea breeze far into the city’s center. After some research I discovered that due to rapid unethical, unnatural, and non indigenous urbanization many parts of the city are on average a degree or two warmer. It’s strange how modernity has cut us off from the breeze of a coastal city.

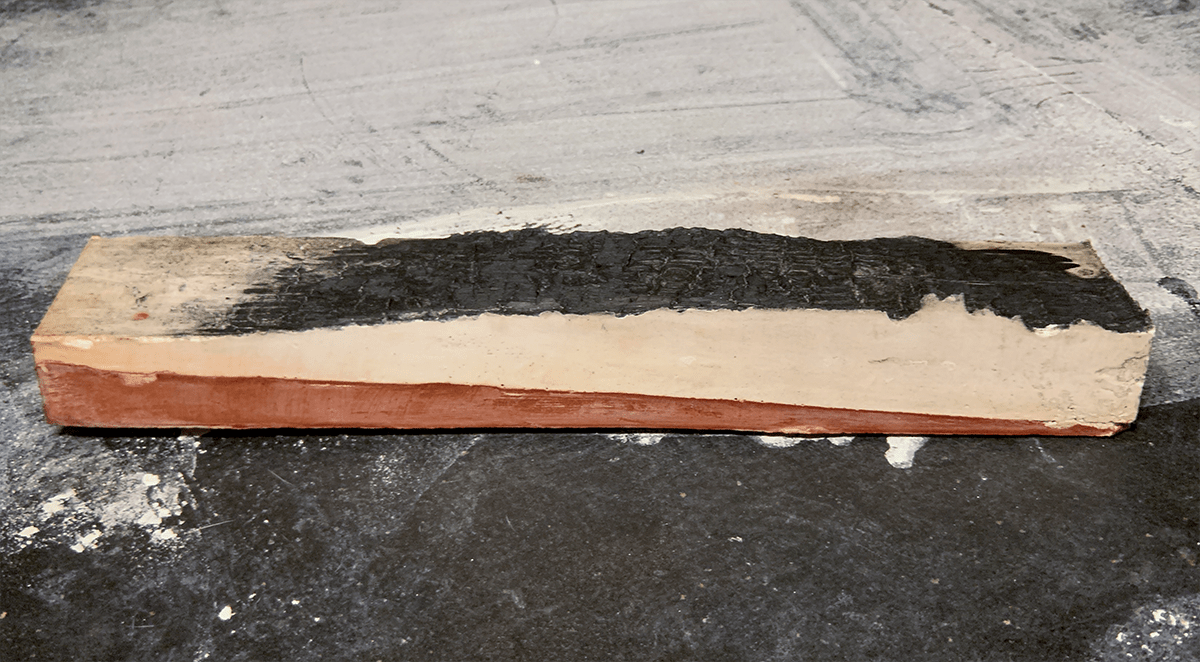

Up on the roof, I found a gold mine of leftover construction materials – slabs of local stone, wood, pipes, wire and concrete – all part of the palette I was working with. Not only does every city dweller interact with these materials on a daily basis, the materials themself are constantly interacting with their environment. Construction materials, depending on where they are in their life cycle, vary in function as different people engage with them. From the construction worker to the building’s inhabitants, the physicality and politics of construction materials is something I have already familiarized myself with formally in a previous project, Karachi Doesn’t Need a Furniture Designer, which can be found on my website.

Karachi is a city that goes through a lot of urban turnover; everywhere you look you will see a construction or demolition taking place. A big state sanctioned demolition being carried out this year is at a katchi abadi known as Gujjar Nala, an area that grew around the banks of a major city drain. Financed by the World Bank under the guise of improving Karachi’s water and sewage system, at least 8000 houses, as well as schools and churches have been knocked down in the area. The work that began in February is in response to urban flooding which took place after the monsoon season in 2020. A recent series of protests saw people gather to try and raise a unified voice against the violence.

Between designing for an architecture firm by day and making objects in my time off, my references vary. From the cruelty of forced demolitions and the devastation of contemporary war ruins, to the ingenuity of bricolage structures all over the city, this assemblage aesthetic is not usually given space in the formal design world. I am interested in how materials come together at construction sites as well as how they break down due to various circumstances.

Along with these images I always work with the canon of modern design history in mind. I wonder: is my inclination toward certain aesthetic decisions solely a result of my training or is there some universal truth to the evolution of this visual language? I am very aware of the duality that exists in my work as I draw from the aesthetics of modern design while critiquing the world it has created.

The history of modern design has long been oriented towards crafting utopic futures. The goal to design for efficiency has taken center stage over peoples’ needs and the industry has turned out to be increasingly profit driven. The design world, shroud in western arrogance, seeks to create the future, but there is an increasing disconnect between those who have the power to design this future and the catastrophe we are hurtling towards.

This series is my interpretation, and subsequent recreation, of this world’s future.

*katchi abadi = Squatter settlements on urban public land. A result of the state’s inability to provide land for housing the burgeon of population, especially those who, pushed by dire economic factors, join the waves of rural-to-urban migration every year.

-

-

-

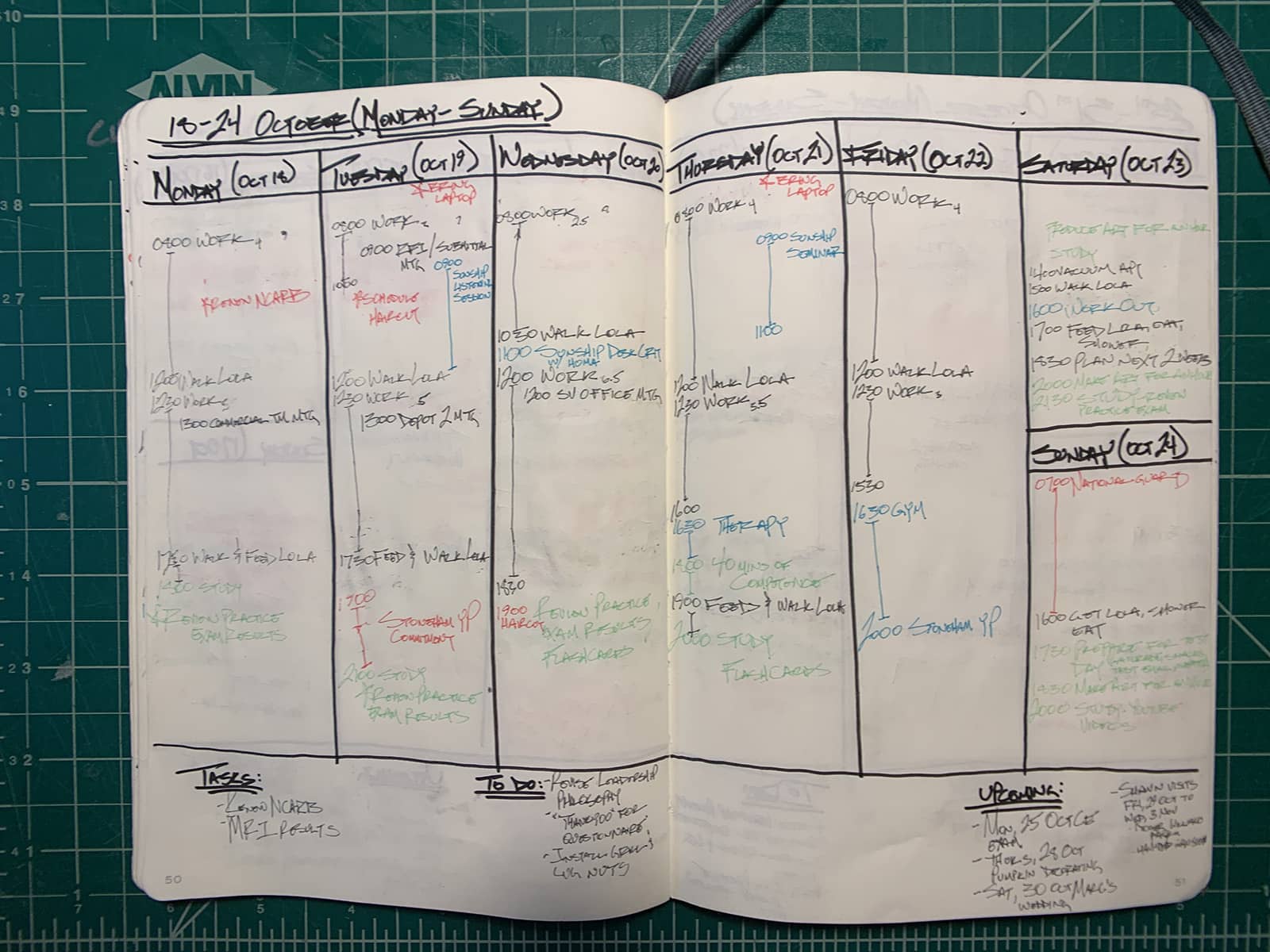

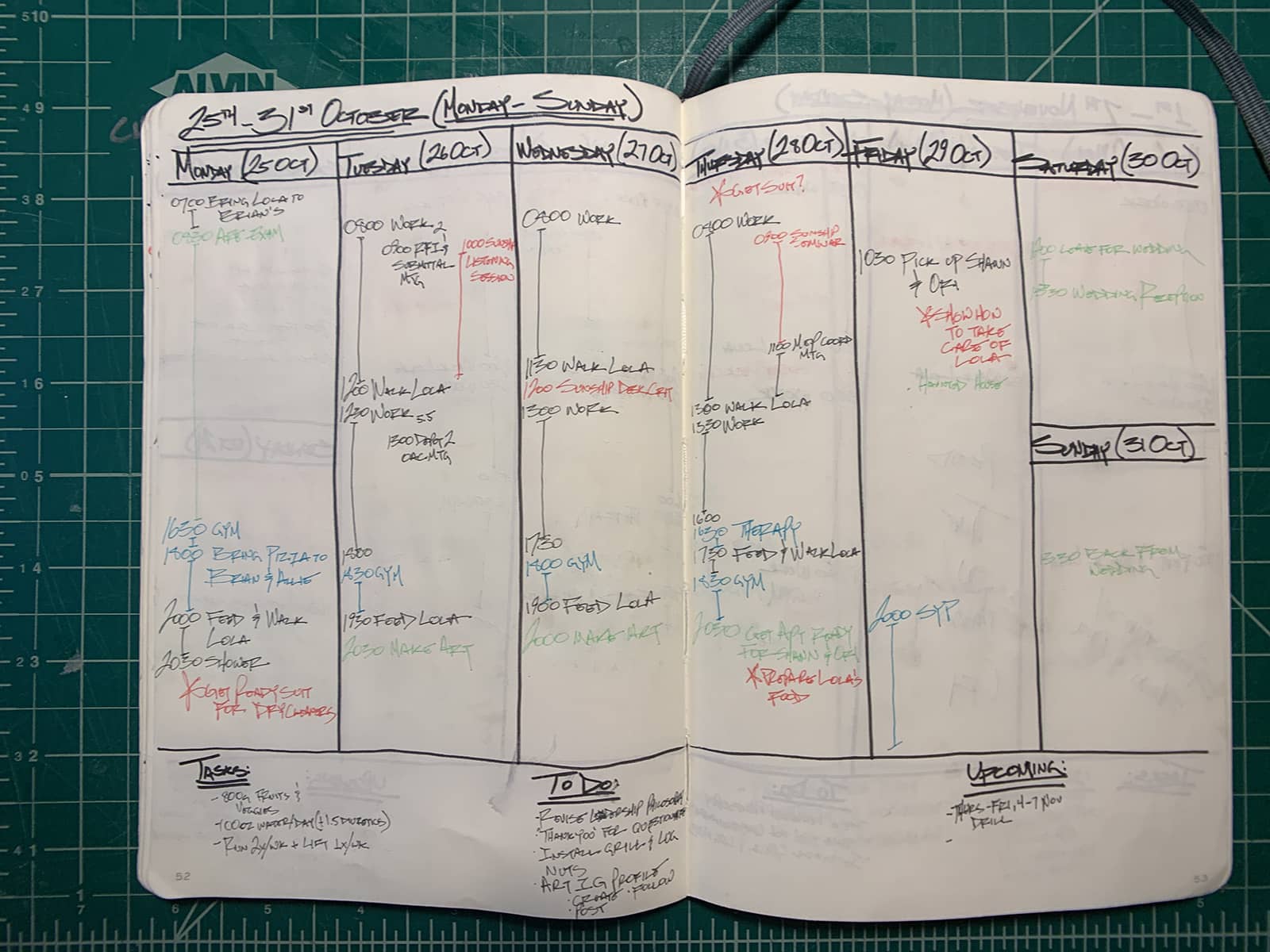

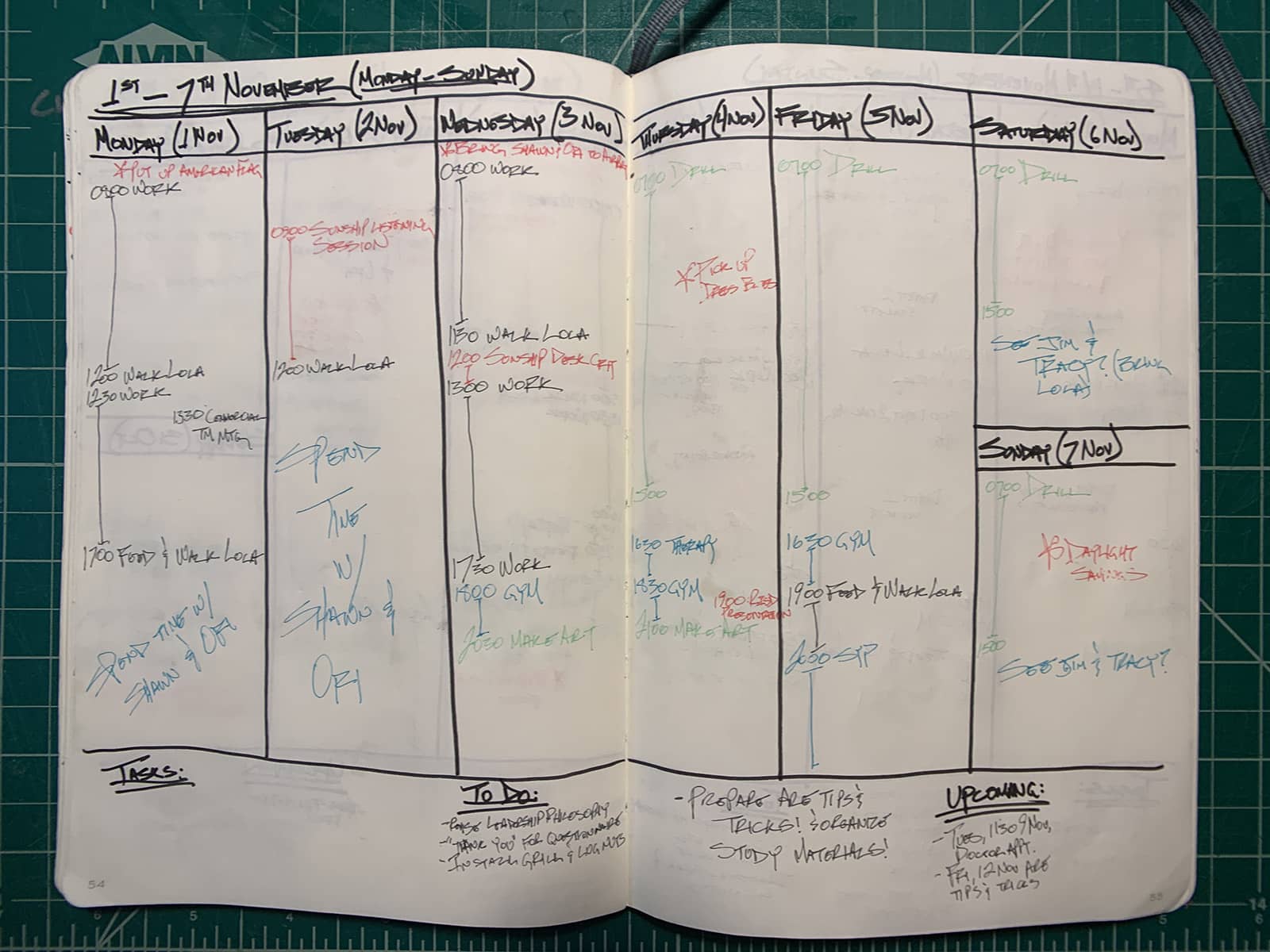

PRACTISE

I started this art residency, my first, with the intention of beginning my art practice, whatever that might look like. I didn’t want to set any expectations or vision of my future work. All I wanted was to start. In fact, I turned my apartment dining room and living room area into a studio. I graduated with an architecture degree from an art school in the summer of 2020 and was lucky enough to find a job north of Boston during major furloughs caused by the COVID epidemic. So right now, I’m transitioning into art and design as my army career tapers down to a part-time commitment towards retirement in 2024, with 21 years total.

I have an extensive but unstable art background where opportunities were torn from my reality numerous times – now, after reestablishing that connection with myself and a community through art school, I am fearful of losing it again.

My biggest problem lately has been starting. I’ve been looking to commence work and there is a sense of urgency, but it’s fleeting as I procrastinate by committing to other tasks like cleaning my apartment, balancing my budget, doing laundry, looking at social media….and even sketching, planning artwork or researching for artwork. There is this resistance to get into the depth of any work; a heaviness to start.

I work full time while studying for the six architectural boards. Although part-time, I am still obligated to the military. I have a girlfriend I love and a wonderful COVID puppy. My schedule is crammed, to say the least, and it’s not going to change. My actual problem is starting. My reason for saying all this is because I must schedule everything in a notebook. Each Friday, I plan out the following week, Monday through Sunday.

So, what did I do? I scheduled the art in. (This past week I didn’t have time to plan out my week, therefore I am noticeably missing or late to appointments.) So, my scheduled work didn’t require a thing. In fact, I didn’t have to do anything. If I committed myself to only making artwork, and sat ready to do that, I was good. So that’s what I did. I sat in my studio for an hour, and I recorded it. I didn’t meditate or nap because that would be doing something other than the work. I didn’t force anything either.

Before my documenting myself working, I was very excited. I am so busy and always racing to the next thing, I couldn’t wait to sit in my studio and do nothing, by that I mean, to work. As I sat there, shifting positions so my butt wouldn’t go numb, I tried to experience my studio space as a volume that I am inhabiting. My mind couldn’t sit still, of course. And the final twenty minutes were difficult. But Lola made it much easier. Lastly, I did have a reaction to going through this hour. The whole time I was sitting there, I was fixated on taking this older concrete cast project out of its mold. It bothered me whenever I saw it.

Because this exercise seemed difficult towards the end, that told me I should repeat this work. This is discipline; this is practice; this is what pros do – they push through and get to that flow state. Also, as you can see, Lola stole the show. I decided to repeat the exercise with her not in the room. Later I realized that it didn’t matter that Lola wasn’t there. I mean, if I am practicing, or working, of course Lola would normally be free to hover around. Naturally, I didn’t put her in dog-jail again after this one time. As my videos progressively become more chaotic, I transition from sitting to impulse. This is a good thing. I sort of want to thrive in the chaos of practice.

For my final video, I decided to do my initial exercise again…I guess to revisit old, familiar experiences. Doing this video, I was very tired and really didn’t want to do it. Surprisingly, the time – just – flew! My experience was that it was much easier sitting around doing nothing for an hour. Moreover, I felt much more relaxed, at ease, and even experiences of increased fulfillment than the first few times doing this. Moreover, I didn’t come out empty-handed. I produced something. It’s something I’m very familiar with doing – decaying material imprints on plaster and concrete casts.

Like a wanderer, I was searching, meandering, obsessing about reaching some sort of enlightenment. I sought answers in books, videos, and people when I wasn’t studying for my architectural boards. “If I solved this trauma…”, “if I learned about how my brain worked…”, “if I picked up on a special ritual…” I started this residency looking for an answer, and at the end I found the answer is, there is no answer.

But I did pick up on valuable tools the past forty days for this residency. I realized that I need to schedule my practice – that’s just the way my brain works. I realized that by scheduling time, sitting around doing nothing in my studio is better than doing something other than my practice. And I realized that if there is so much to do and I don’t have time, I can make more time by slowing down.

The Ark is the last architecture before The Flood and the first architecture after The Flood; a hinge between two worlds. What if the Ark is an Arc in Time—Arc as in a curve—slowing time, aligning it with Life Time? The Flood would not be a destructive event, but a place of and for life.

“SunShip Thesis” presents works created as part of Arts Letters and Numbers’ two six-week immersive virtual studio programs led by David Gersten and Homa Shojaie. “SunShip Thesis” is a space of creative exchange and inquiry into the nature of the human condition and imagining and creating exploratory works. Each of the participants raised their questions and pursued their voices within a space of poetic imagination. These studio programs were held as part of “SunShip: The Arc That Makes The Flood Possible,” Arts Letters & Numbers’ exhibition in the CityX Venice Italian Virtual Pavilion of the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale.